sounding

6 August - 1 September 2005

Liverpool Street Gallery

“Where the great whales come sailing by/ Sail and sail/ With unshut eye.” [1]

Unlike any other ocean creature, whales arouse a yearning in humans. They are like sirens, calling us to the deep blue, coaxing us towards a better and more spiritual place. It is the mass, surface, blubber and beauty of whales that attract and inspire Peter Sharp.

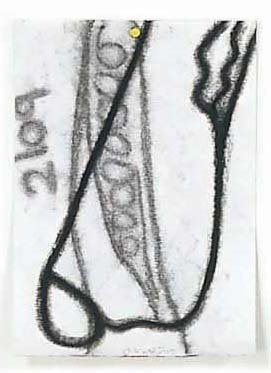

His current body of work has been informed by his experiences of nature - as a surfer at Kurnell, as a fisherman and through his discovery of a beached whale carcass at Albany, Western Australia, in 2003. During this pivotal visit to Western Australia, Peter Sharp made many drawings of whale bones found in a disused whaling station. He made abstract charcoal sketches which are repeatedly drawn and rubbed back and which evoke the calming power of these enormous mammals.

His abstractions in paint, charcoal, sculpture or in print allow the viewer the space for individual imagination. The whale skeletons, their silhouettes, their shadows and tactile surface textures offer an inherent suggestion of secret experience, of an underwater silence and the gyre-like cycles of life and death. Whale teeth larger than the average human skull are superimposed with simple drawings of archetypal whale shapes. The enormity of these creatures induces us to contemplate our own mortality and purpose: Man...with all his god-like intellect which has penetrated into the movements and constitution of the solar system – with all these exalted powers – still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin. [2]

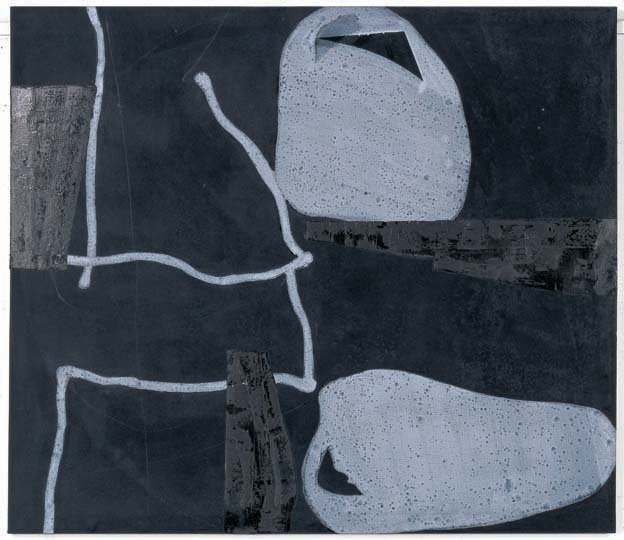

When Sharp first happened upon the whale carcass and a room of bones he was confronted by the stench of rotting blubber and a graveyard of shoulder parts, fin bones and broken vertebrae. But in the works, particularly the paintings, those experiences have been expanded to the wider context of tentacles, water-drops, carbon dioxide bubbles, masked bone shapes, water running over flesh, taut skin and a salty water womb.

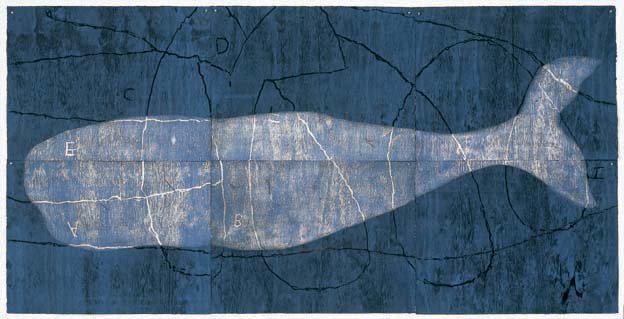

Herman Melville’s 1851 tale Moby Dick introduced Sharp to certain grisly whaling processes. Disinclined to be drawn in to the book’s awe-inspiring and fearful narrative, Sharp incorporated the diagrams on flensing (cutting up the whale, much like peeling an orange) into his powerful woodcut and carbarundum prints. In his ambitious print, Heads or Tails, Peter collaborated with print technician Brenda Tye. He quickly painted the negative whale image in PVA glue then sprinkled on the carbarundum to achieve a velvety black surface. Then they printed a woodcut of the imposing flensing diagram over the top. They chose the colours of 19th century Willow-pattern china to complement the historical aspect of the Moby Dick tale.

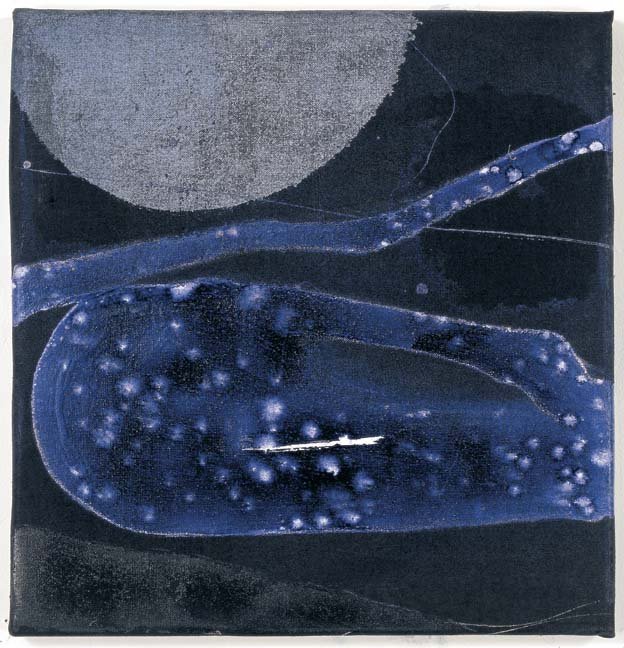

The artist’s ability to create a sense of fathomless depth, both literally and emotionally, is most obvious in the compositions of his paintings Whale 3 and Making Scrimshaw. Scrimshaws were made by 19th century sailors who carved naive images into whale teeth and then rubbed them with ink.

Sharp paints on stretched and sealed linen laid on the floor. Starting with a flourish of acrylic paint, sometimes poured straight from the can, he then applies layers of oil glaze. Gravity contributes to the stained and bleeding appearance of the paint. Peter enjoys this method as it reminds him of the movement of tides and allows him an overview of the work-in-progress.

Sharp’s paintings are rich explorations of texture and simple shapes. They are further developed by his use of cut-outs to test the effectiveness of the ambiguous forms. Circles and semi circles are pinned onto the linen, à la Matisse. These sharper preter-natural forms, which are also used in the shelf-pieces, are the dynamics that separate Peter as an abstract artist from more representational landscape painters and add a higher level of visual sophistication.

Sharp’s vision is also informed by the philosophy of Aboriginal artists and their all-encompassing engagement with the land. Peter is interested in the challenges of maintaining a dialogue between non-Indigenous and Indigenous abstract painters who are inextricably linked to the Australian landscape and surrounding oceans. These challenges involve looking beyond the superficial surfaces and seeing x-ray views, cross sections, molecular microcosms and amoebic details.

In 2001, whilst in residence at Darwin University, Sharp was painting with members of the Balgo community when he was approached by an Aboriginal woman. She slapped him on the stomach and said ‘You got your story in you. You gotta get on with it. Paint what you know.’ The sea and the plethora of natural debris that the tides bring in is what Sharp knows. He is rigorous in his desire to work through problems, search for answers and unravel complex feelings both as an individual and as part of a community. It is this energy and sense of discovery that makes his work so evocative and absorbing.

-Prue Gibson, 2005

_________________

1. Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) The forsaken Merman, Arthur Quiller-Couch, ed. 1919. The Oxford Book of English Verse: 1250–1900.

2. Charles Darwin, The descent of man, 1st ed. J. Murray, London, 1871.

Harpoon, 2005, oil and acrylic on linen, 150 x 200cm

Shelf Work, Moby, 2005, 8 panels and 3 found objects, shelf length 210cm

Whaling Station, 2005, carborundum print on six sheets 1/3, 134 x 267cm

Drawings, 2004, charcoal on paper

Albatross

Heads or Tails

Making Scrimshaw

Scrimshaw

Scuttle

Sounding

Whale 3

Whale Bone 16

Whale Bone 17

Whale Bone 18

Whale Bone 19

Whale Bone 20

Whale Bone 21

Whale Bone 22

Whale Bone 23

Whale Bone 24

Whale Bone 25