How to draw trees

18 August - 09 September 2017

Liverpool Street Gallery

how to draw trees:

Take paper, charcoal and an eraser if you must.

Leave town.

Drive west.

Drive till the earth turns red and the scrub dry and the towns

intermittent.

Cobar.

Keep. Driving.

Take paper, charcoal and an eraser if you must.

Past Mario’s, with its famous lacework balcony and slag heap views.

Past Mutawintji Road, and the burned out, flipped over car on Silver City Highway.

This must be the place. 1200km west.

Take paper, charcoal and an eraser if you must.

Find a shady spot, maybe under the dappled shade of a riverbed ghost gum. Sit for a while.

Look.

And listen.

Sit for longer than feels comfortable, longer than you think you should.

Take paper, charcoal and an eraser if you must.

Look at the forms of the leaves and branches that shade you, and the shapes they make when they hit the ground.

Squint until fallen matter becomes one with fallen shadow in the viscous caverns of your eyes.

Take paper, charcoal and an eraser if you must. Sit until your fingers are itching to draw.

Then sit a bit longer.

With eyes open, and then shut.

Forget everything you’ve learned.

Forget perspective, composition and accuracy.

Forget classicism, modernism and formalism.

Think about shapes in nature, slowing down time and looking – not interpreting. Try to see this place as if for the first time.

Open your eyes.

Pick up the charcoal and press it to paper. Move quickly, before you start remembering again.

-

It was only after Peter Sharp had been making an annual pilgrimage to Fowlers Gap research station for many years that he picked up the charcoal and started to draw.

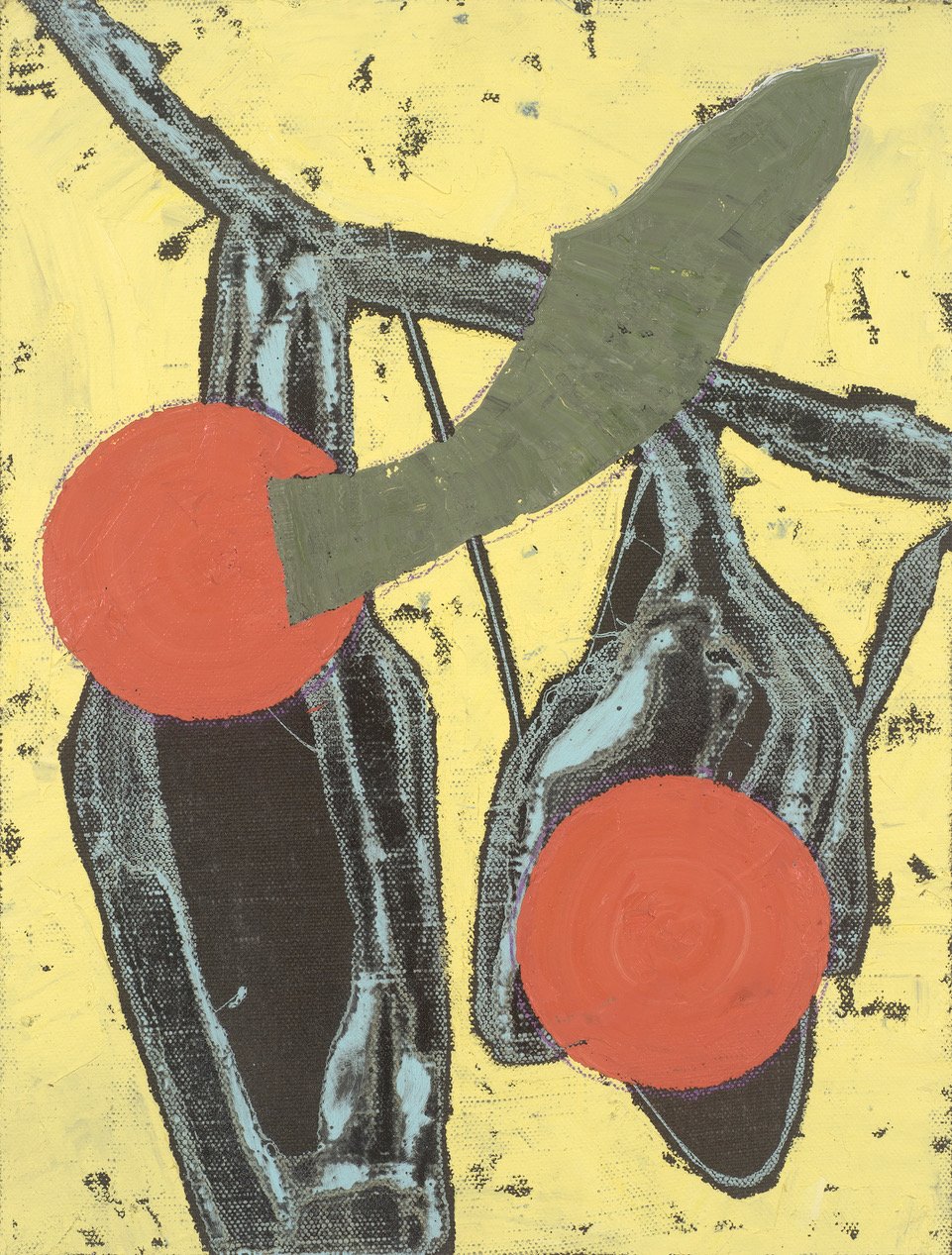

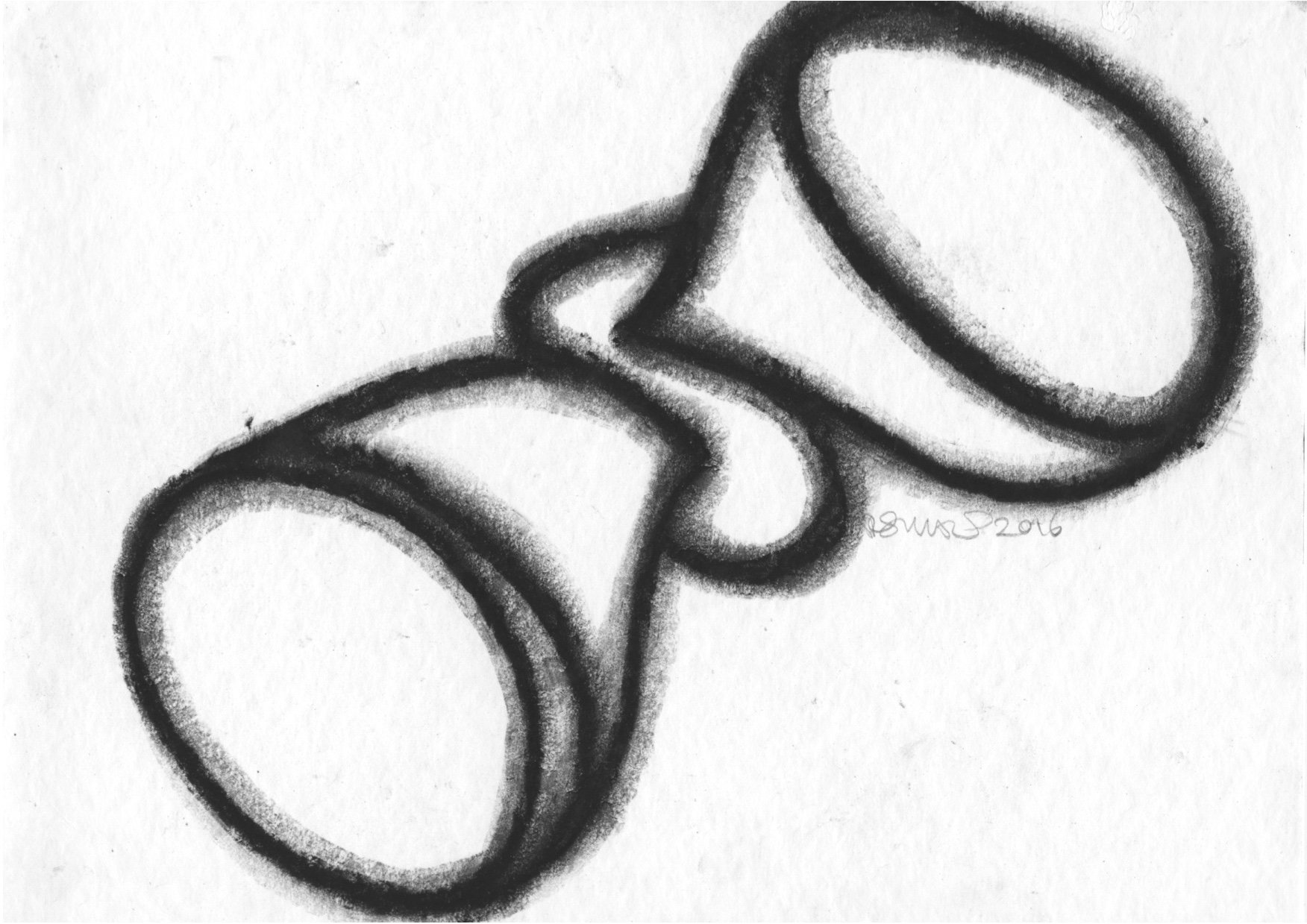

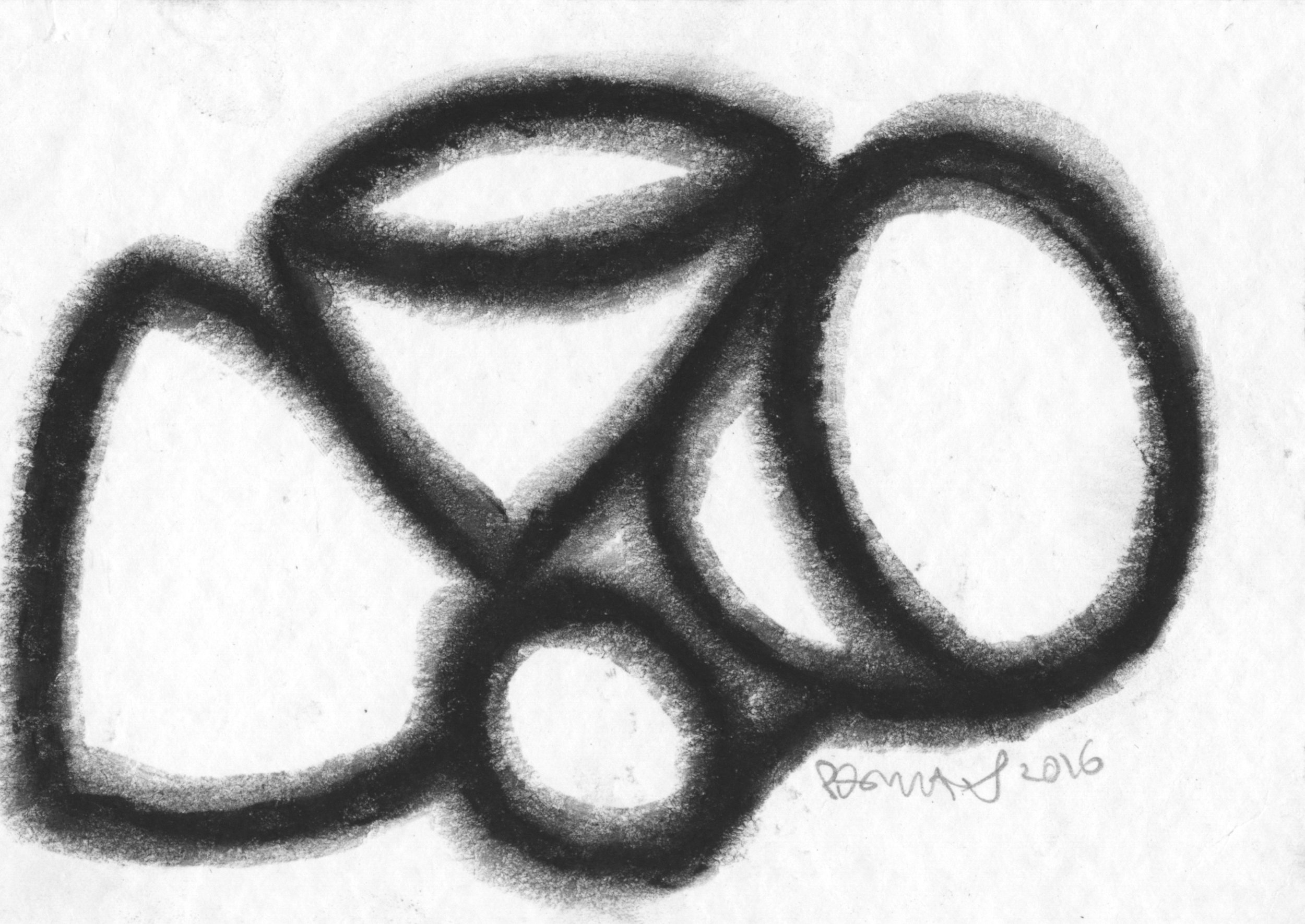

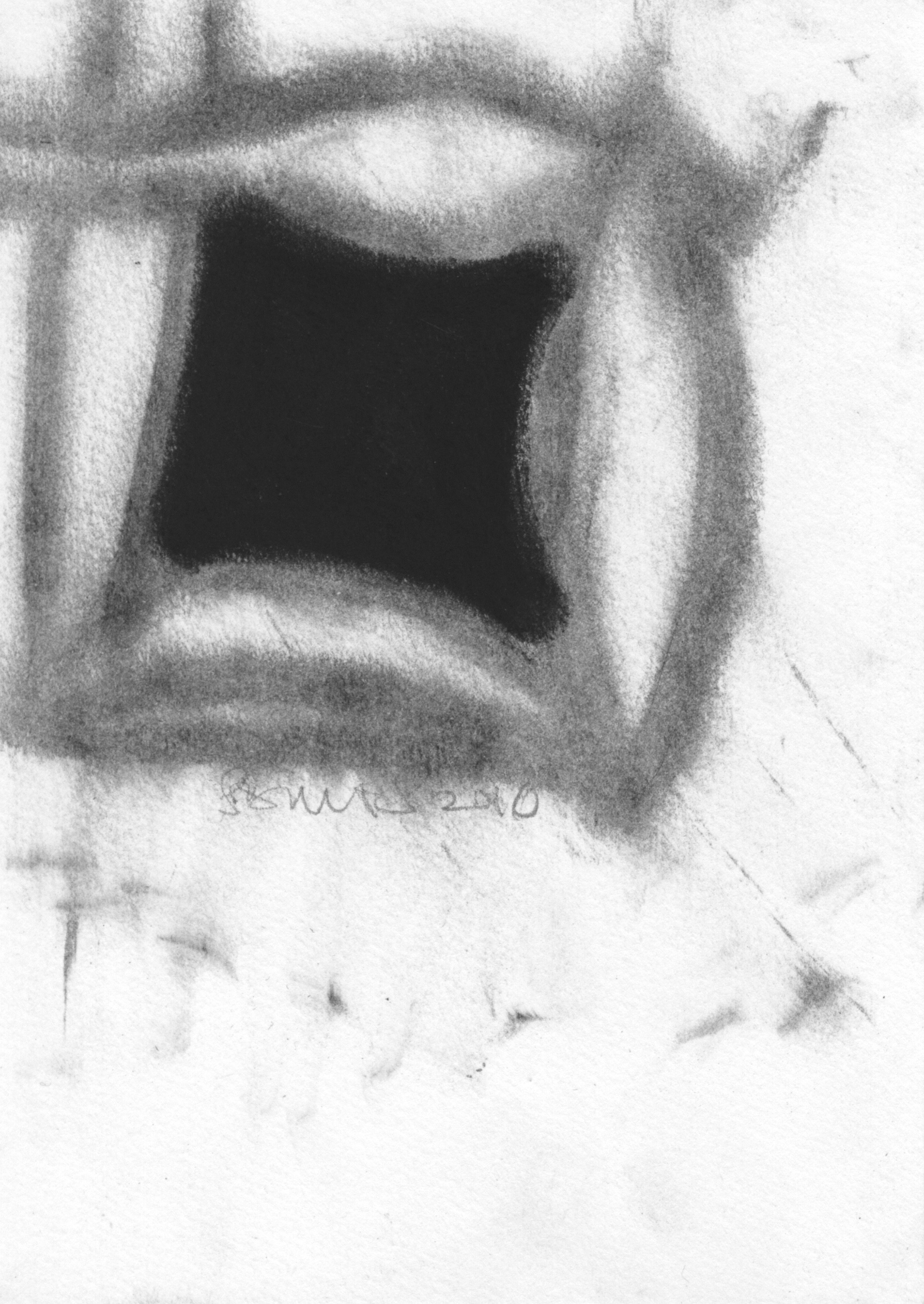

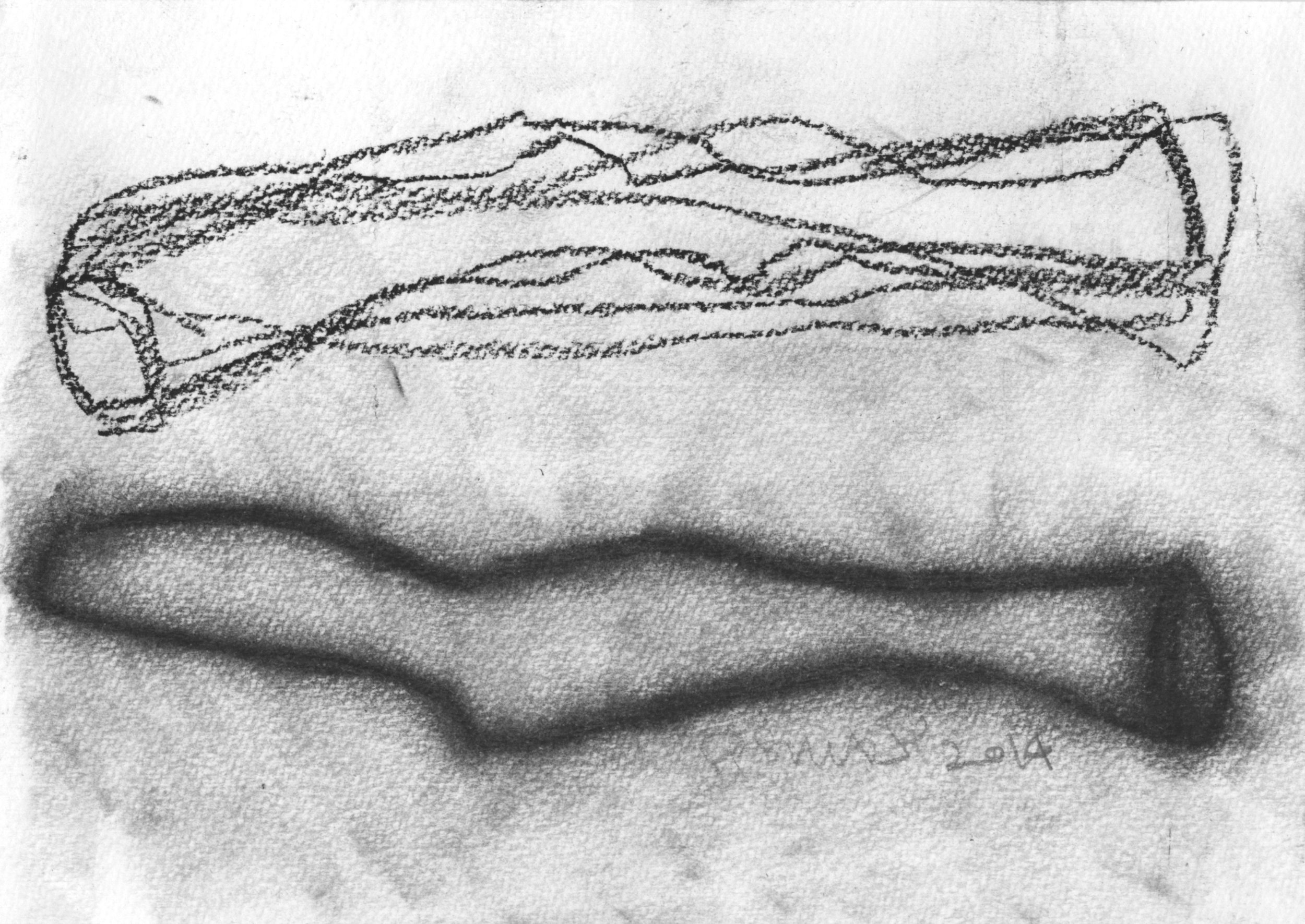

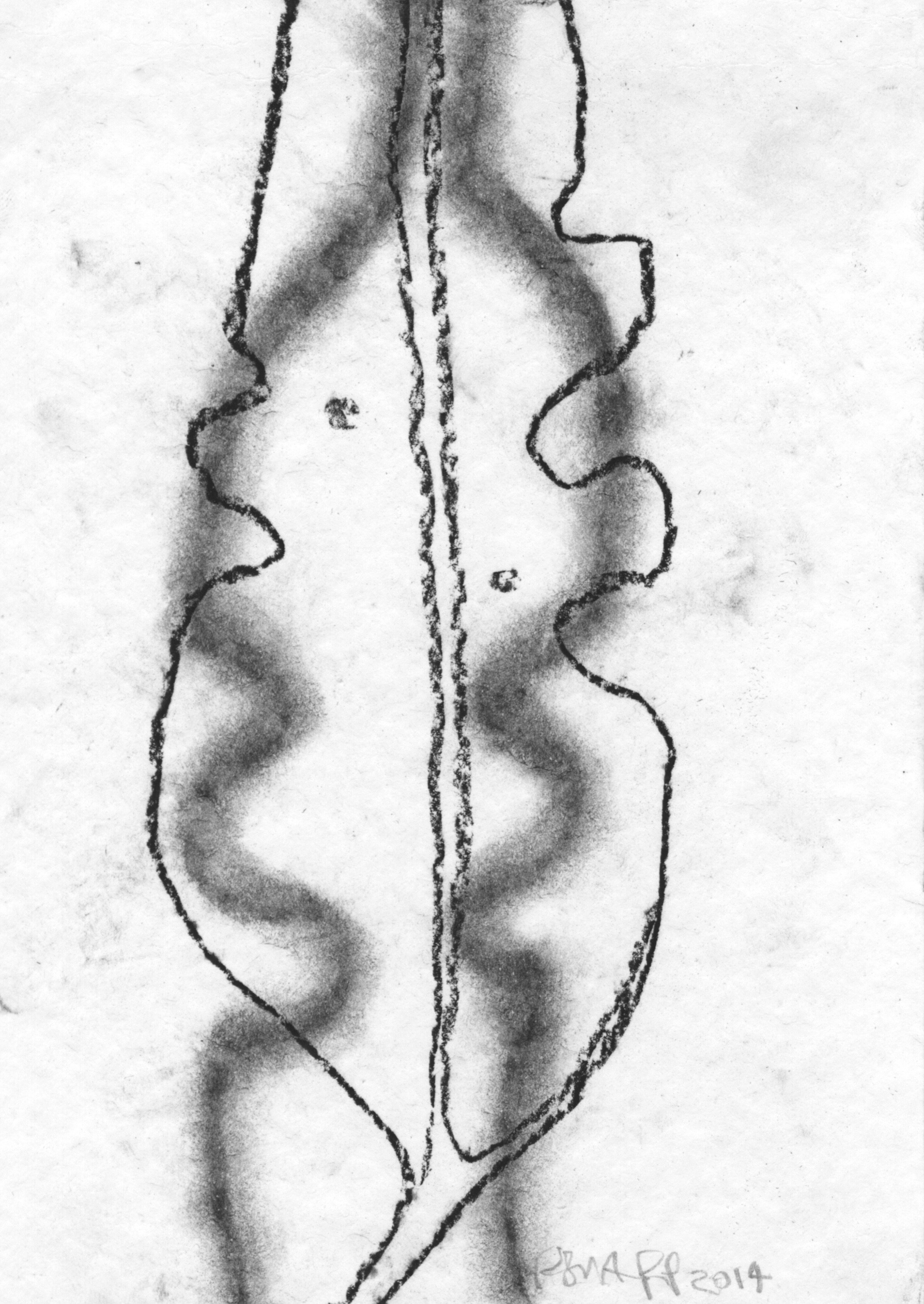

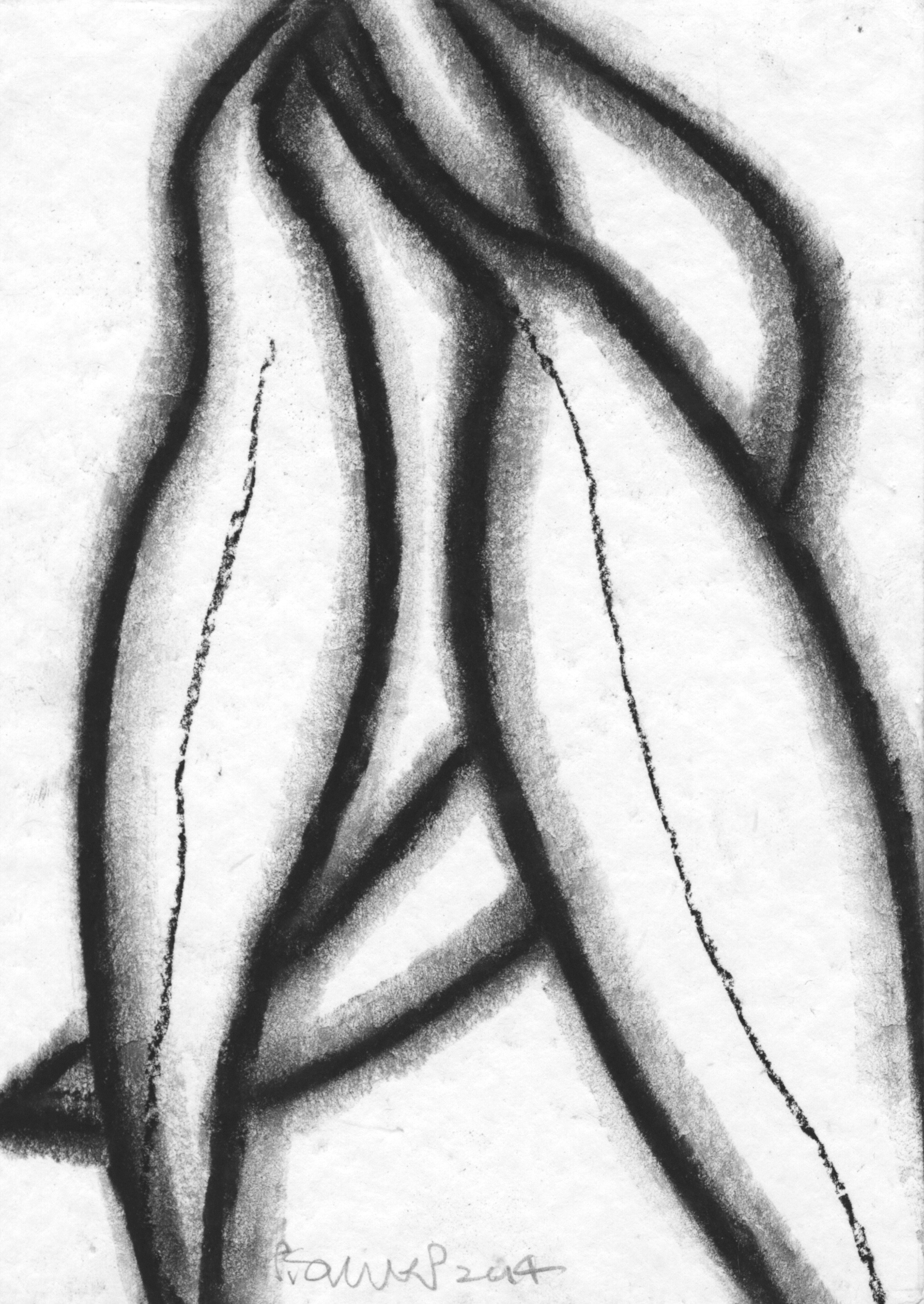

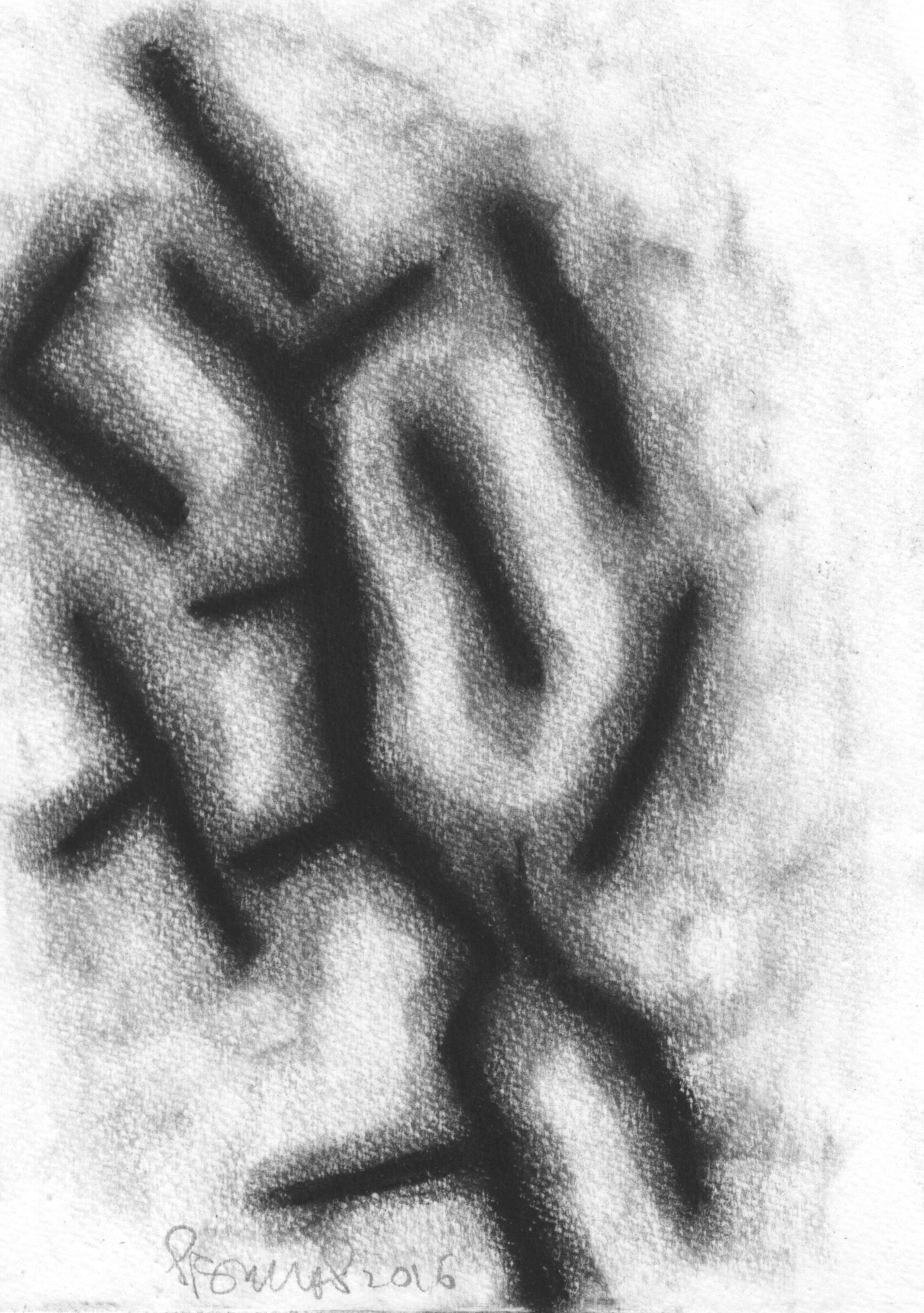

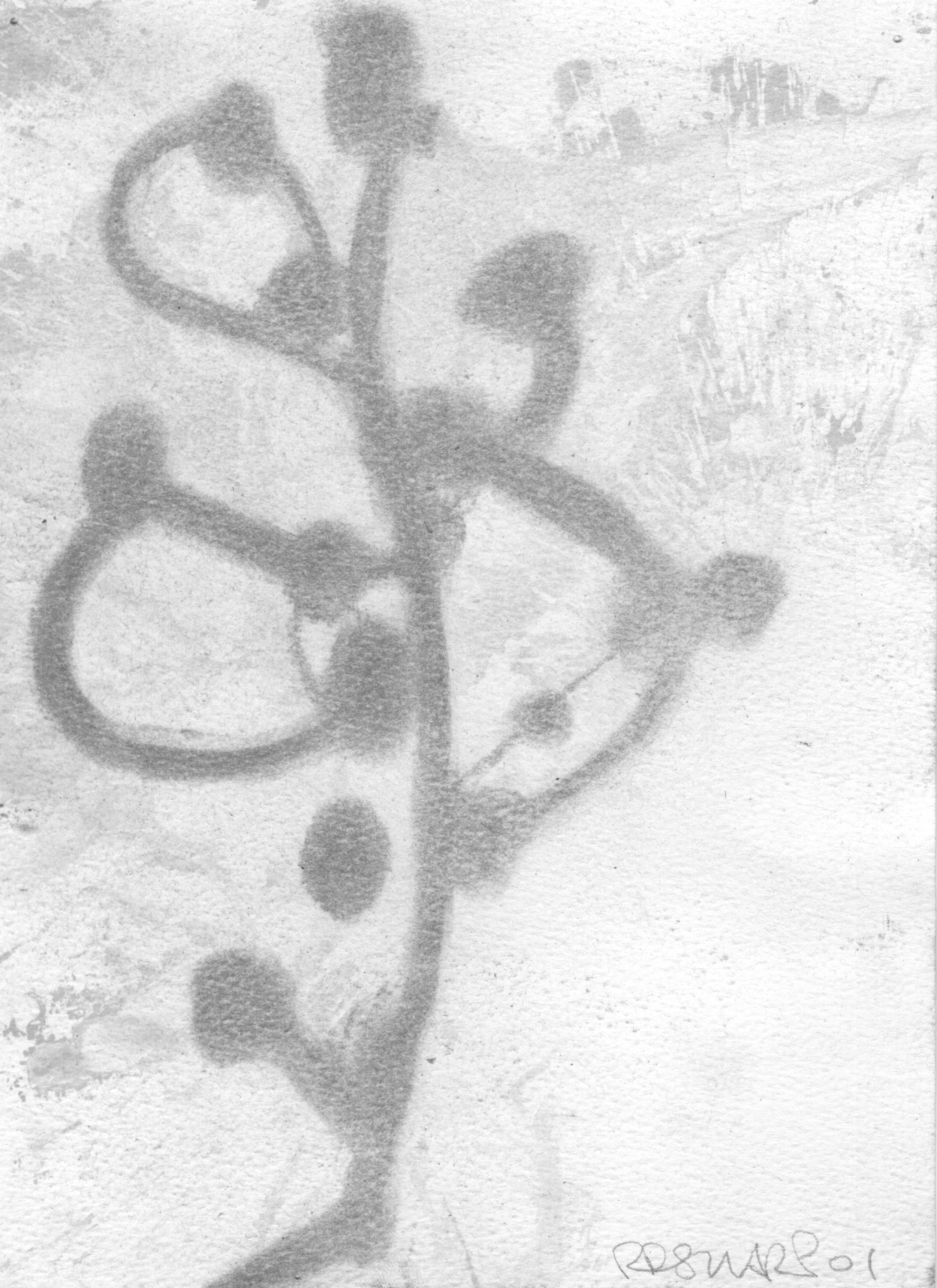

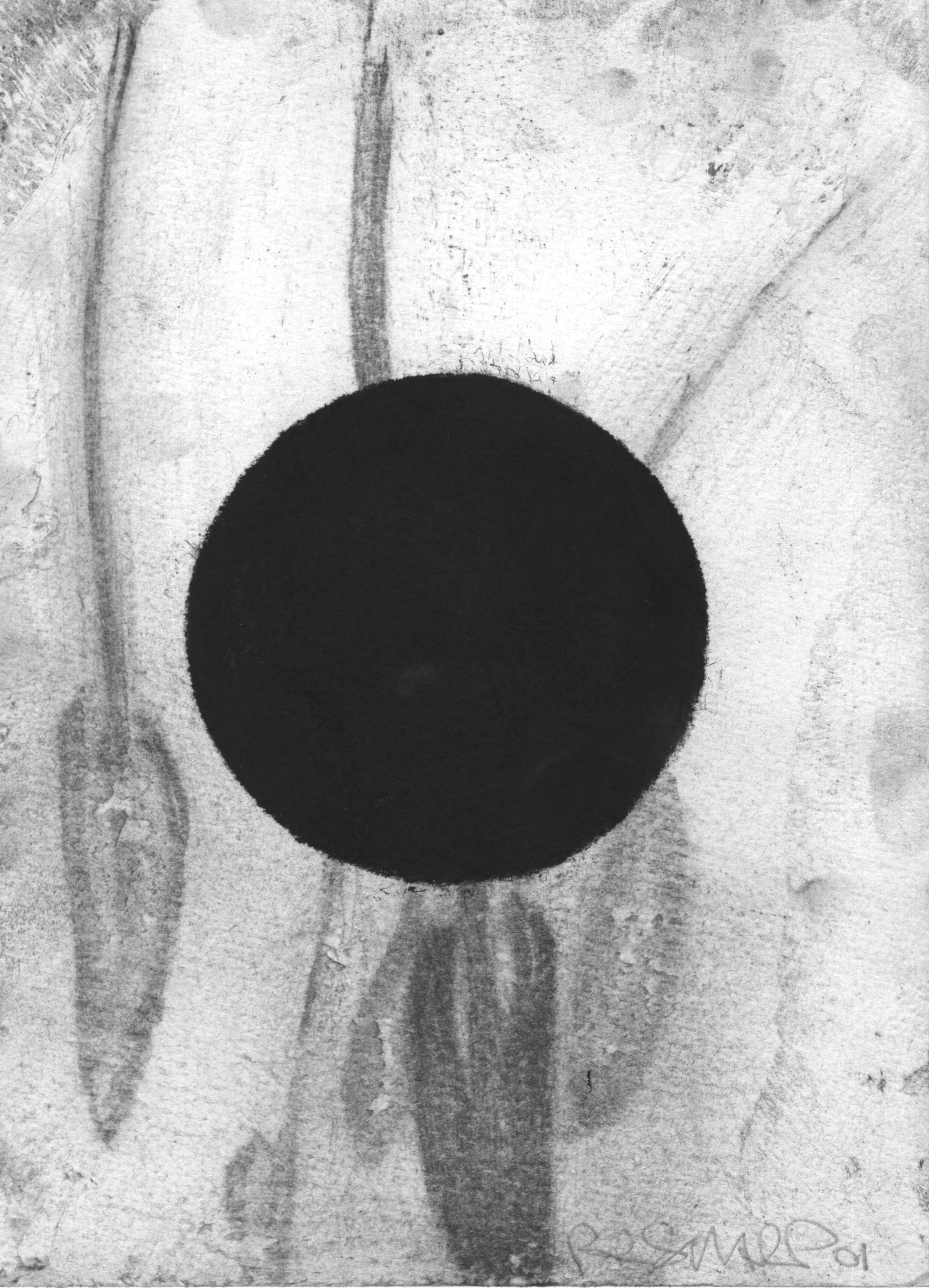

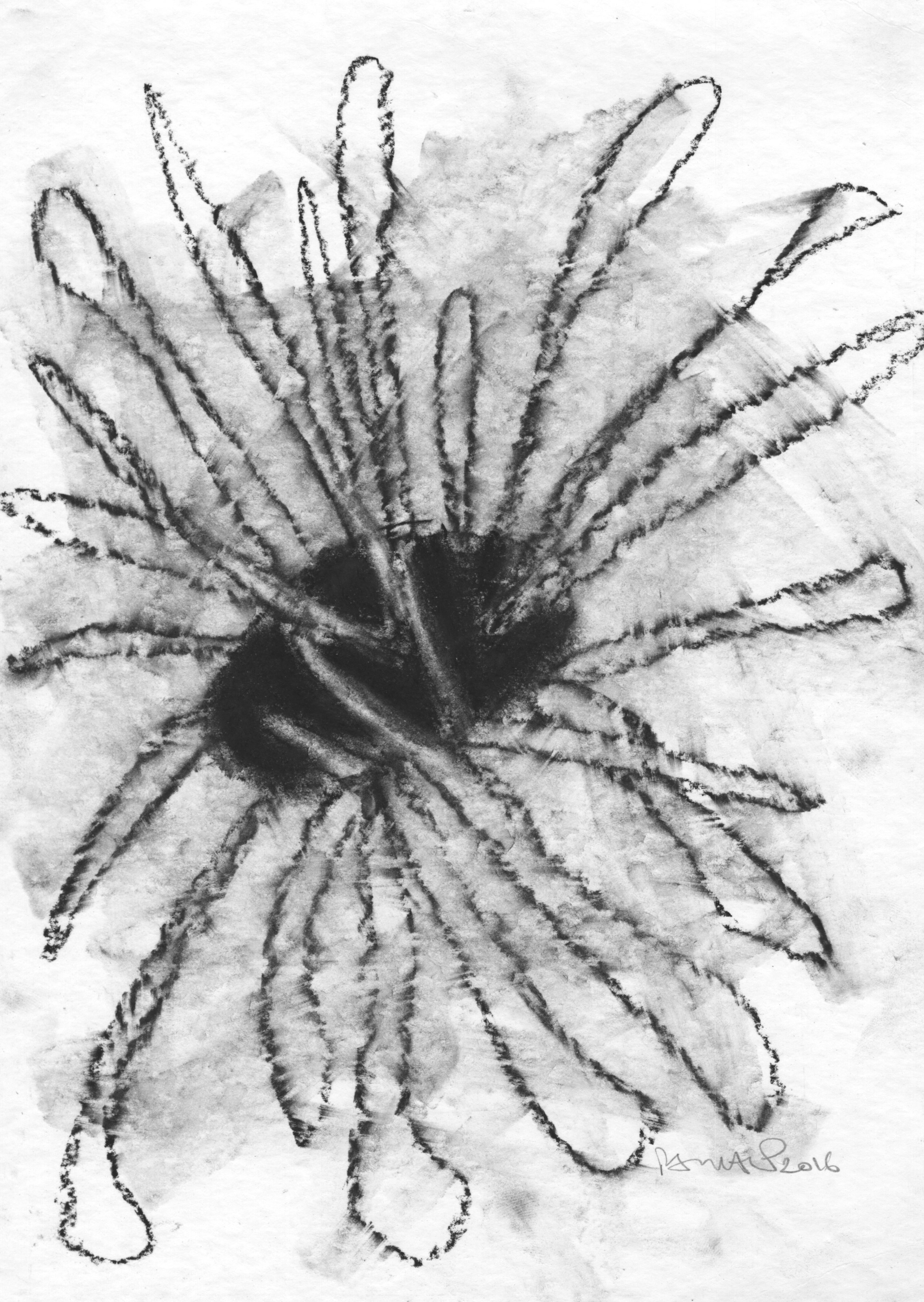

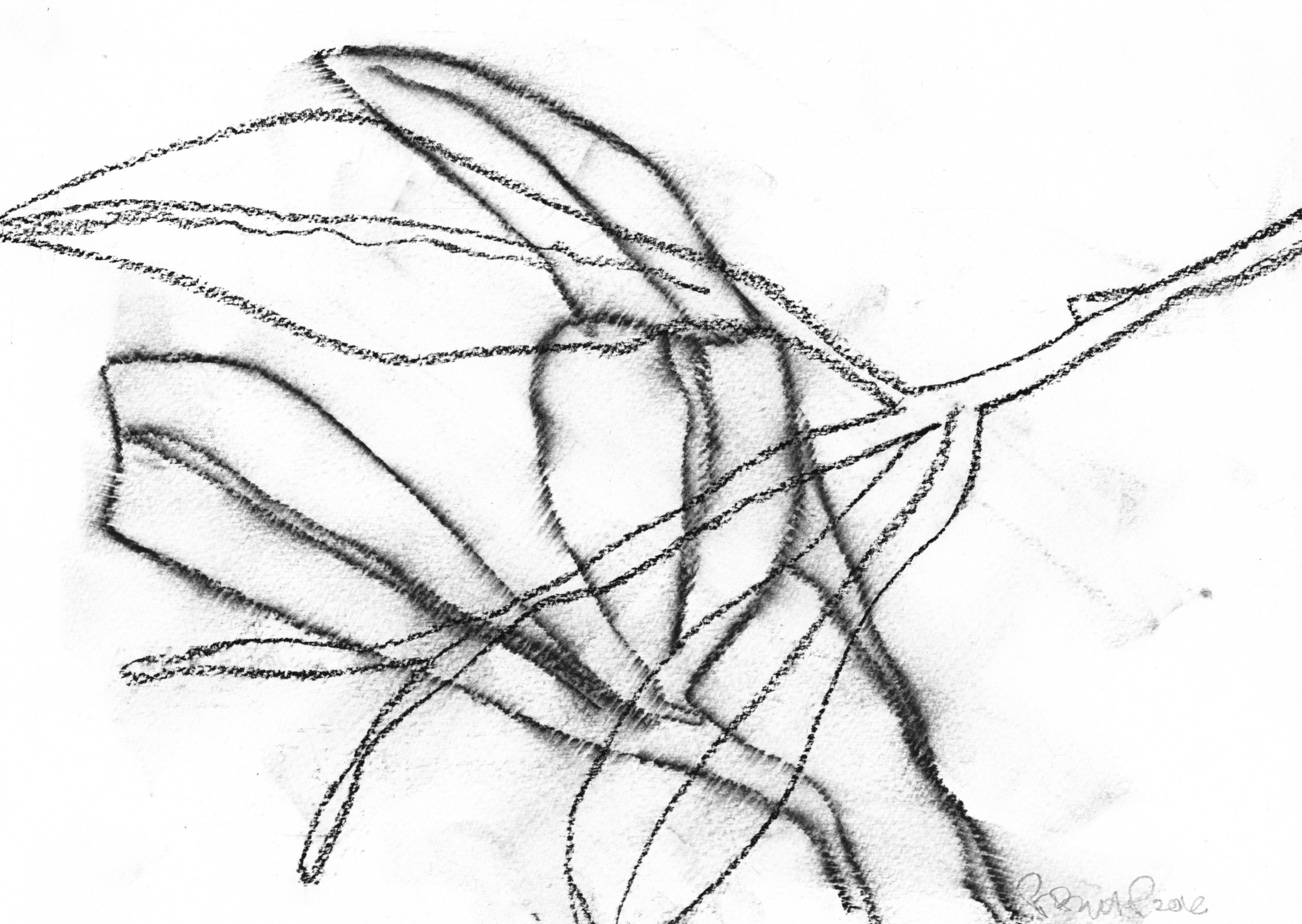

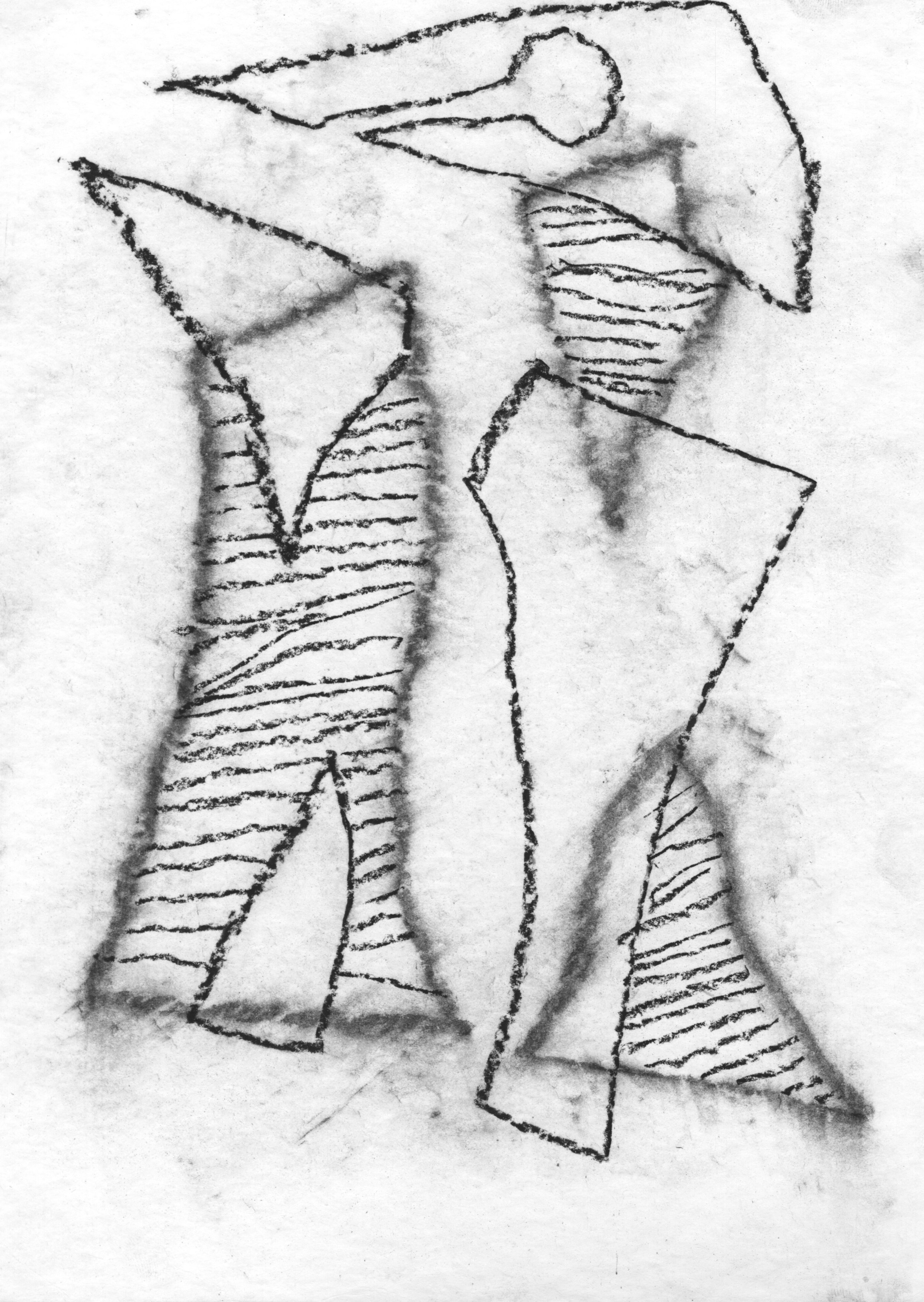

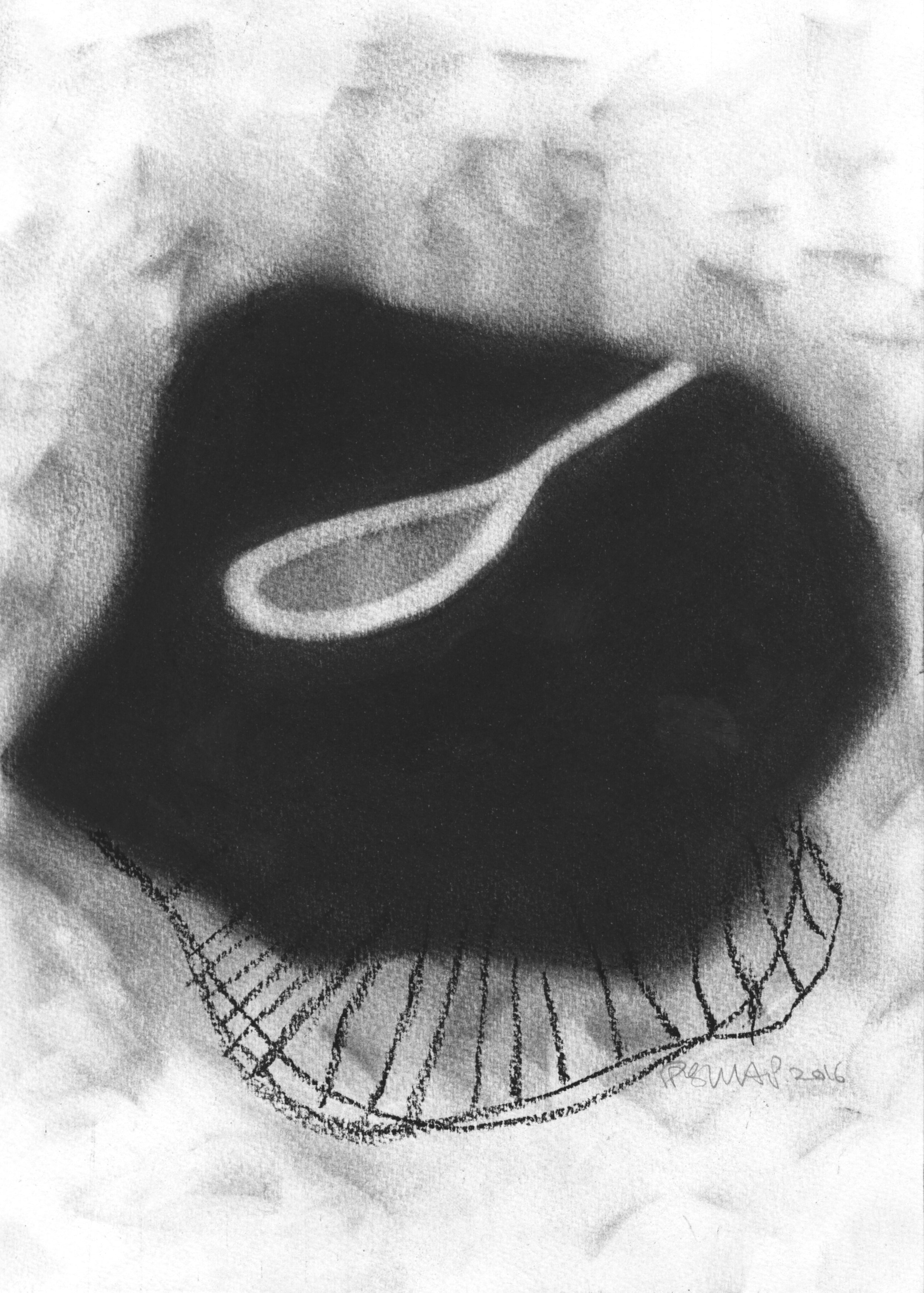

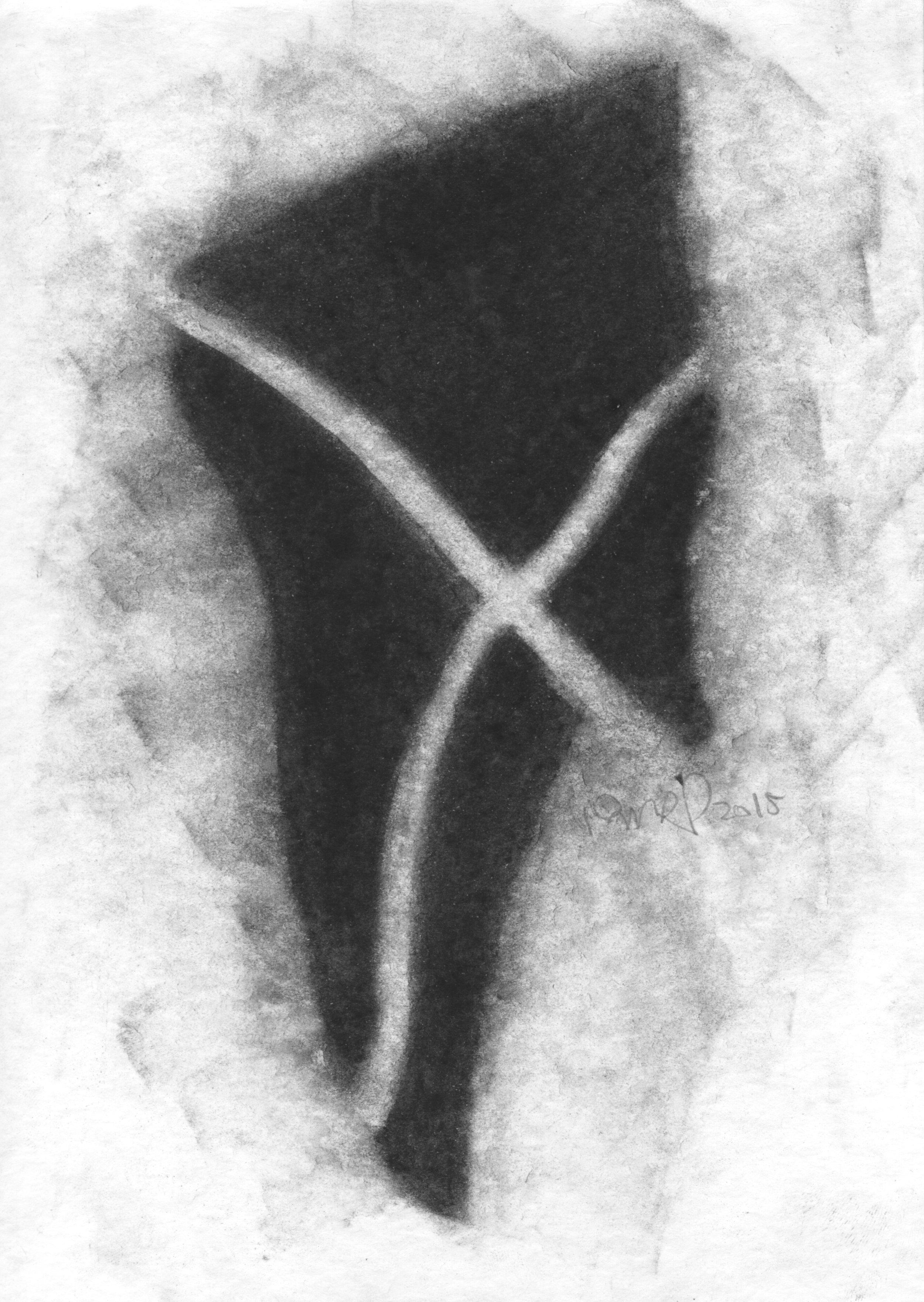

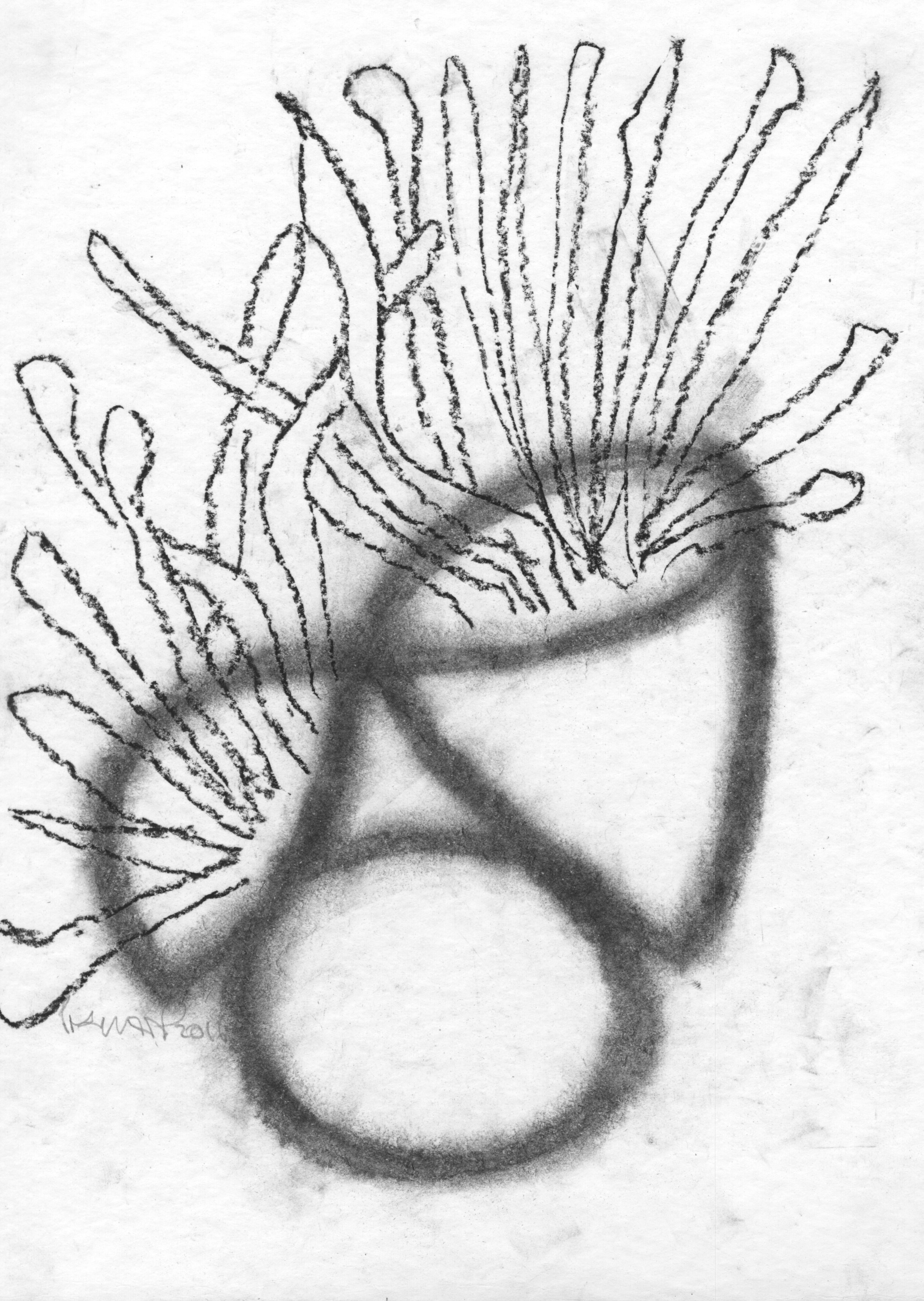

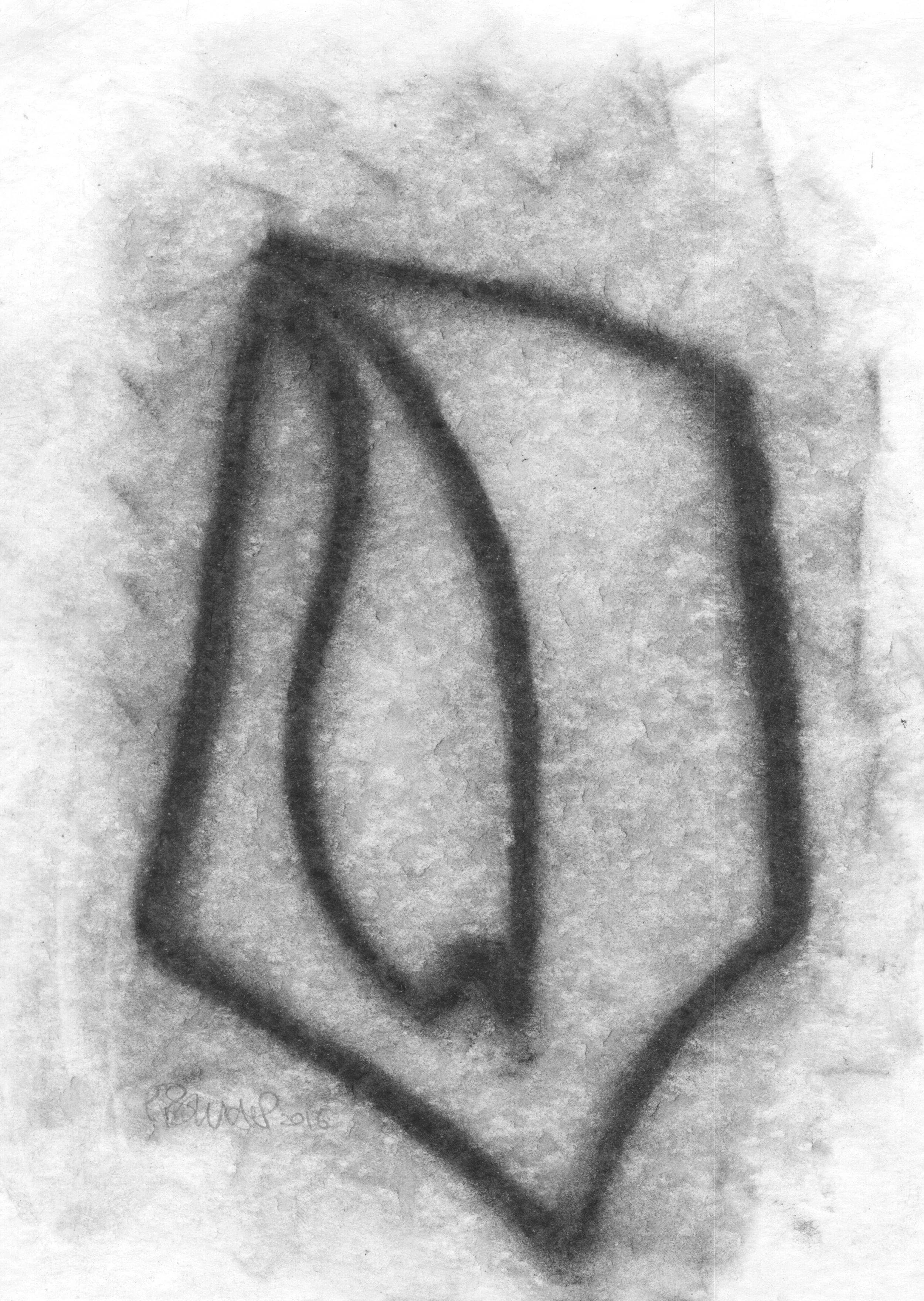

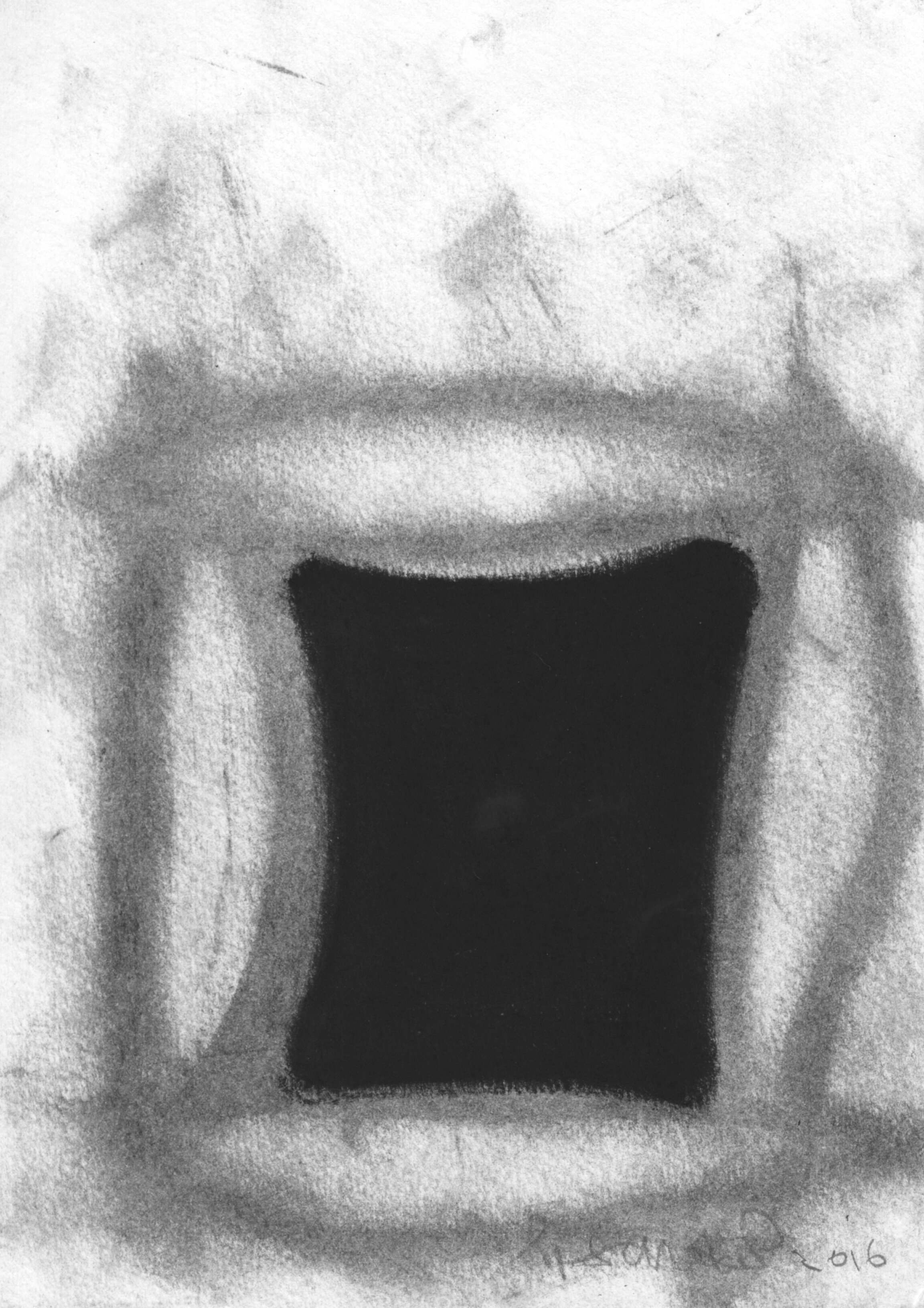

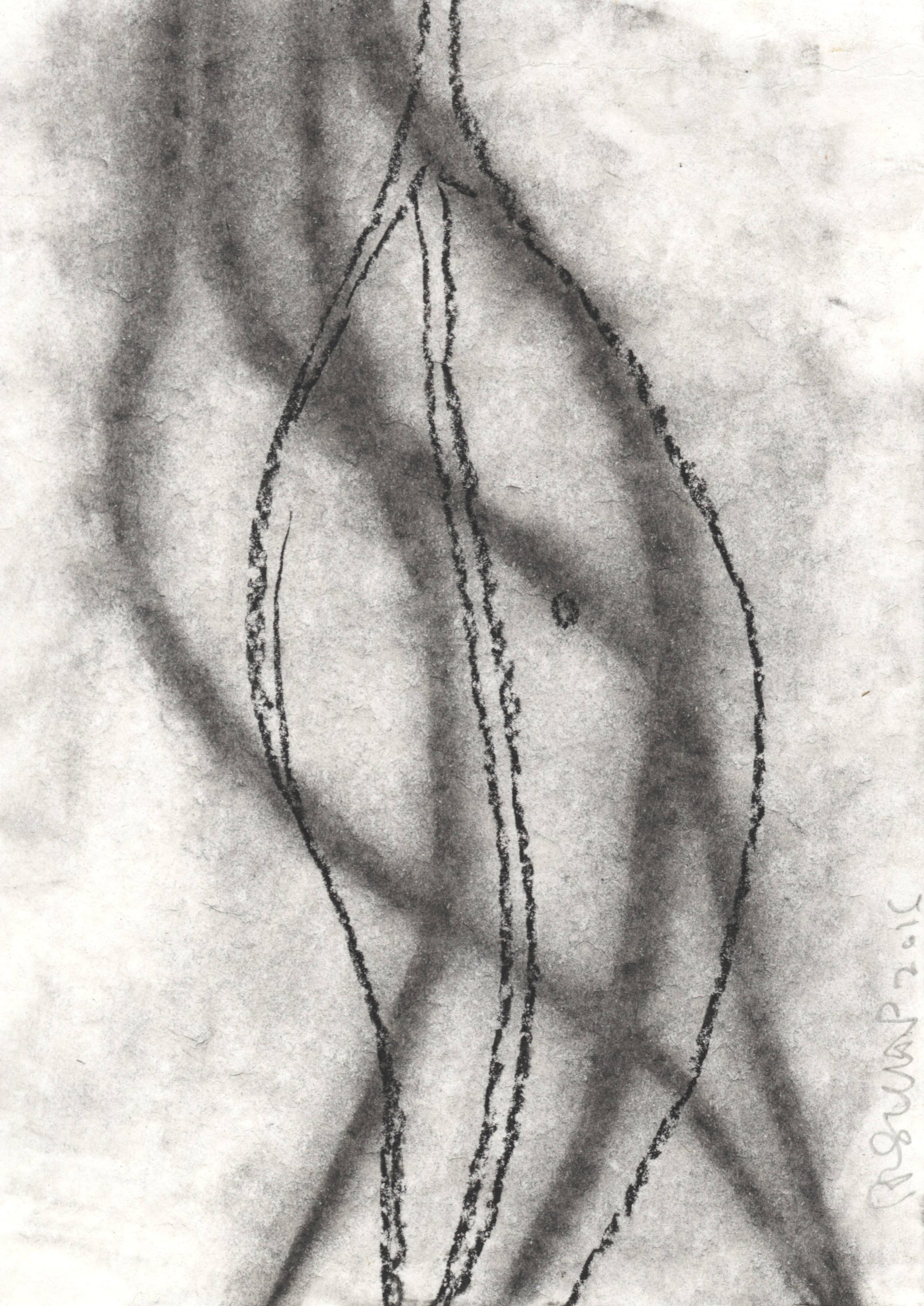

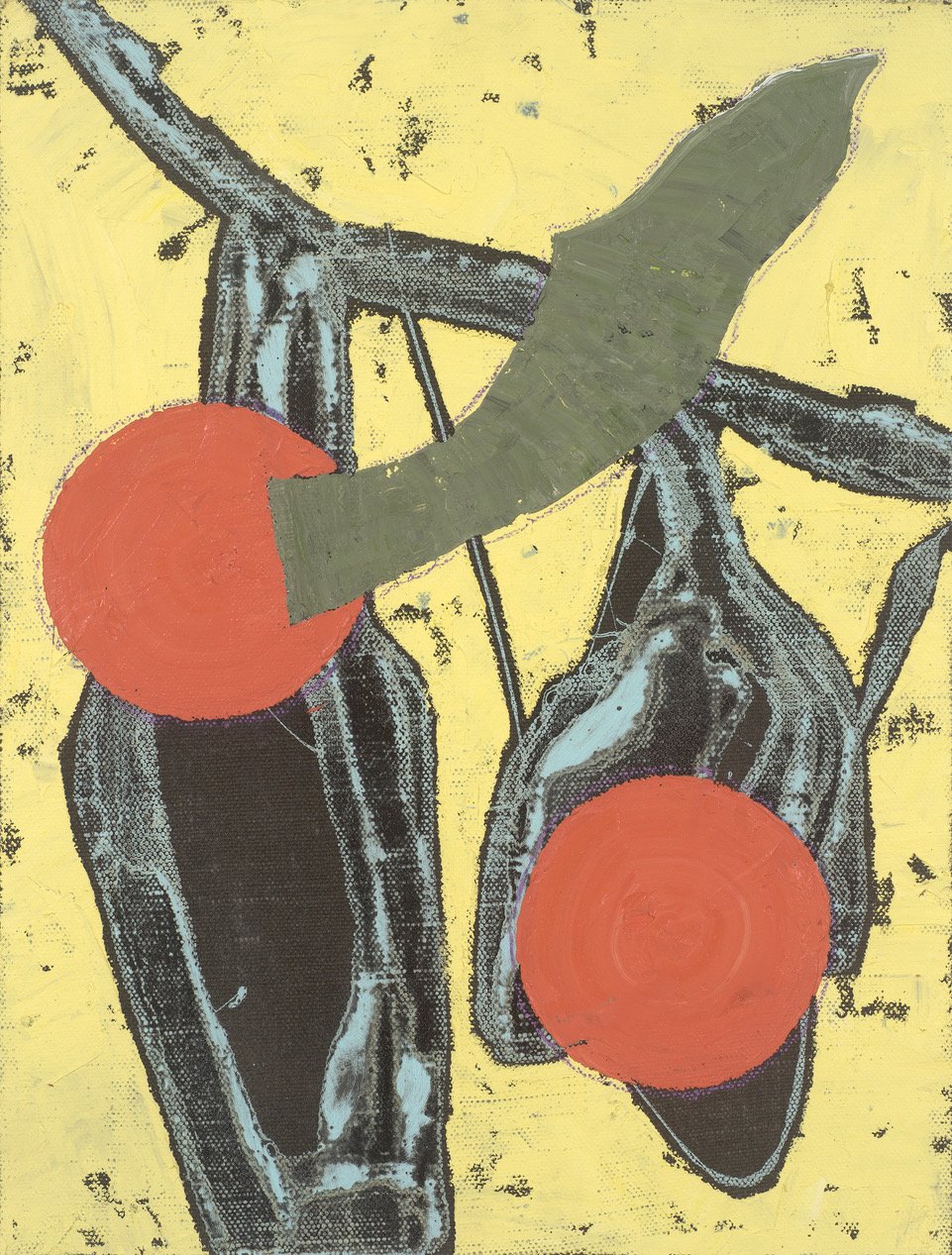

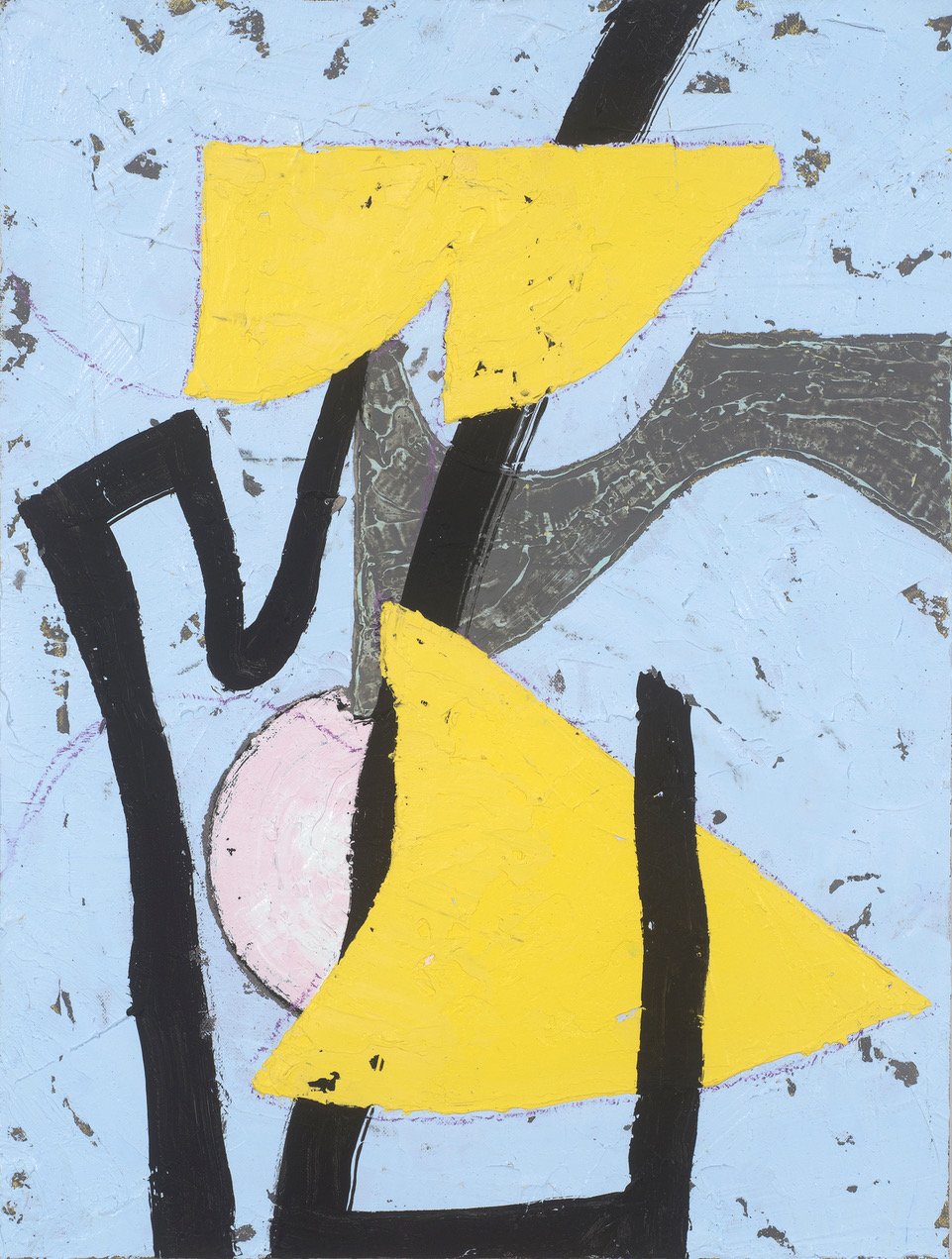

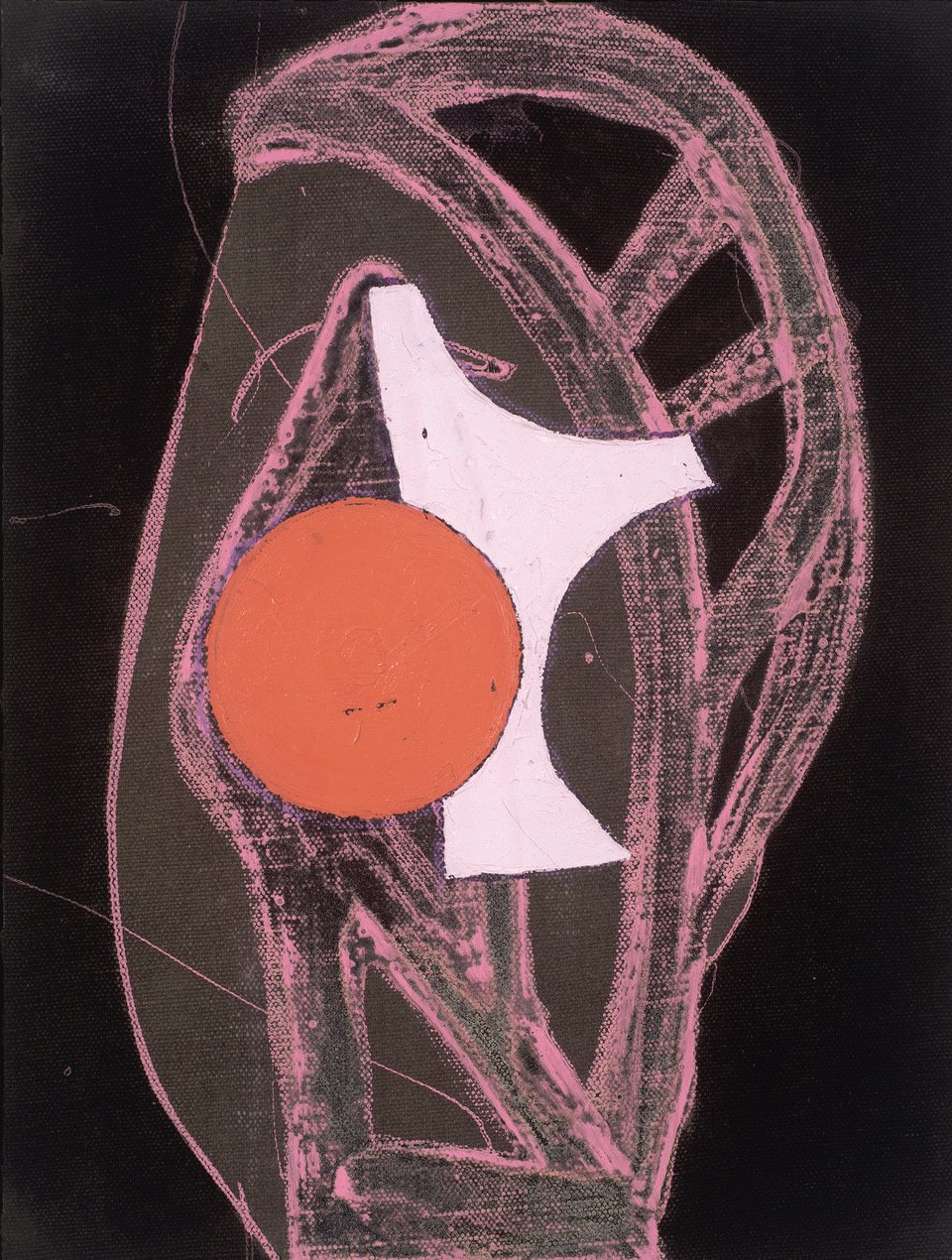

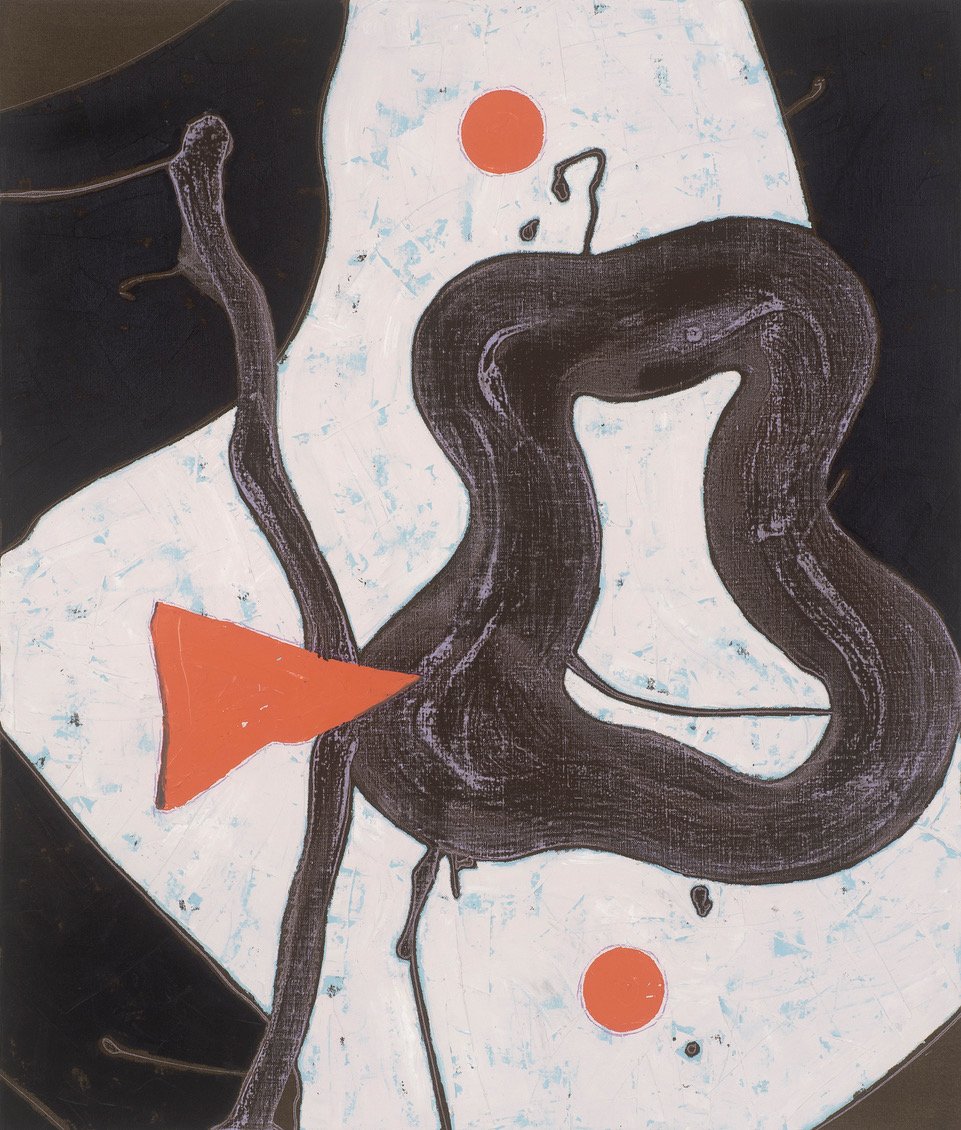

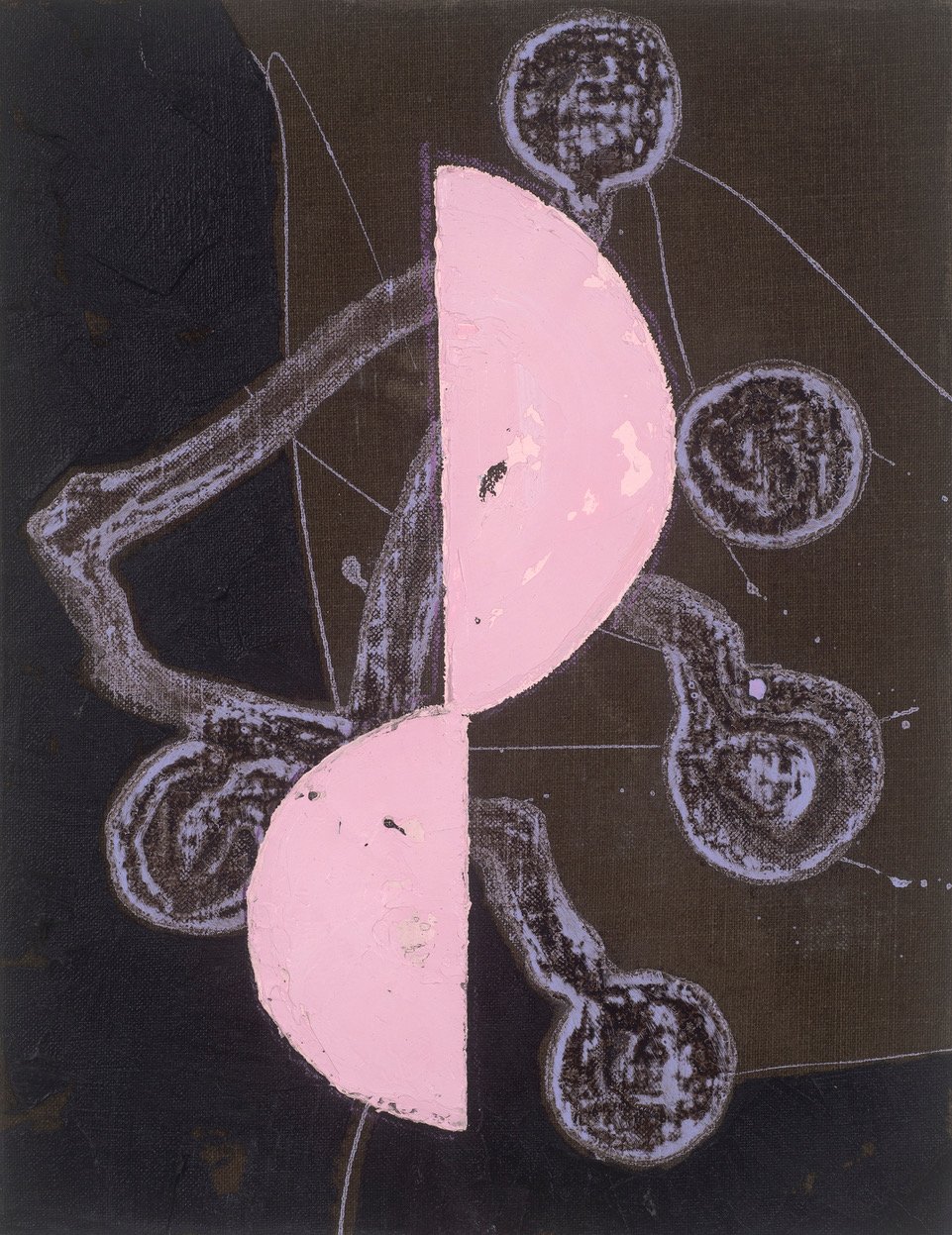

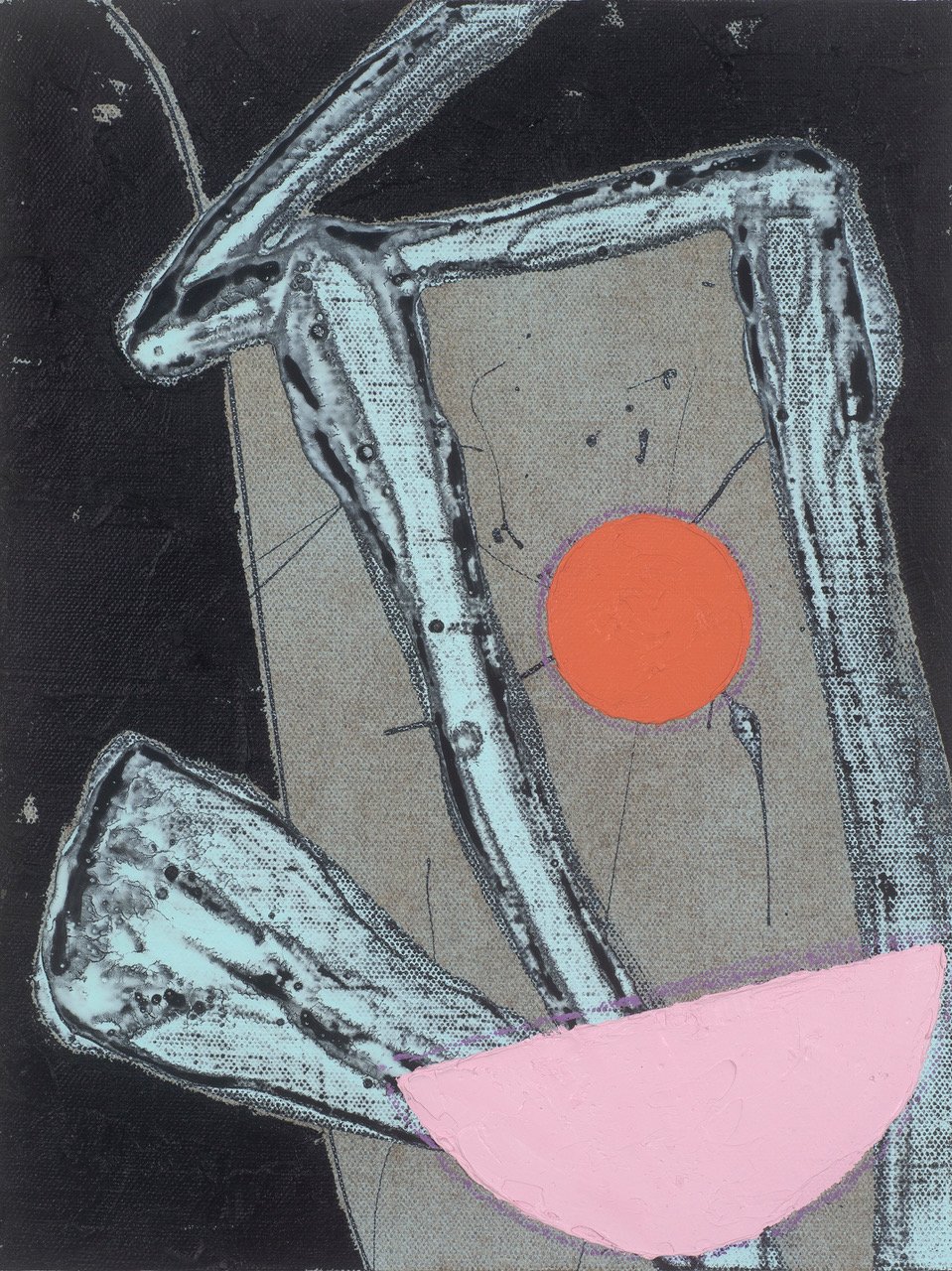

The drawings are modest, depicting leaves, branches, flowers and gumnuts. They are on small pieces of paper, a little under A4 size: ideal for notating in the field. Some feature dense black outlines; in others, a more light-handed charcoal line blackens the peaks but doesn’t fill the valleys of the toothy paper. In these works, the shadows and branches are so gently rendered that it feels as if they might still move in the breeze. As if, like the landscape itself, the drawn lines might be slightly different every time you look at them.

Occasionally Sharp takes drawings back to the quarters and scrubs the charcoal off in the sink – an editing process, and, more prosaically, an act of resource preservation many kilometres from the nearest shop. The top layer of charcoal marks rinses off, leaving stains tattooed in the paper, and streaks where the released particles resettle lightly. Certain works still contain the traces of this action, of erasure and reworking, of mistakes turned into ghostly but indelible impressions. Errors and failures become part of a visible working-out process. Sharp seems to acknowledge that he doesn’t always have the answer, and that introducing an element of chance can produce a better result than intention and precision.

The drawings are understated. Rather than working in traditions of romanticised and representational Australian landscape painting, Sharp comes closer to the schematisation of Fred Williams and the abstracted plains of Rover Thomas. In Sharp’s work as in Williams’, landscape is flattened to the two-dimensional field of the canvas or paper, in a rejection of illusions of depth and perspective. Trees become patterns, and not in a superficial sense; more in a sense of finding rhythm and stripping things back to their basic elements.

From Rover Thomas, Paddy Bedford and other East Kimberley Indigenous artists, Sharp learned of a way of looking at the land that is far removed from the systems of knowledge he was trained in. The work of Thomas in particular, with its depiction of specific landmarks in a style aesthetically congruent with modernist abstraction, presents a way in which land can be understood and expressed beyond realism or representation. Learning about Indigenous connection to and representation of country opened Sharp’s eyes to ways of seeing the land other than those inherited through his experience as a fine-art trained, urban Anglo-Australian. As a result, rather than depicting the landscape, his drawings describe a way of being in this semi-arid zone, and the experience of learning to see it up close.

Through learning to draw trees, Sharp is training himself out of his formal schooling: the drawings are way of unlearning. Of forgetting single-point perspective and the illusion of depth. Composition, transcription and accuracy. Of rejecting the need to get it right the first time, or to master the landscape. In these drawings, object and shadow are collapsed. Leaves and plant fragments are cropped and enlarged dramatically to create abstract fields. These fragmentary views, when pinned in sequence on a large wall, create one unified image. This reflects the way in which, when looking at a large object like a tree up close, we see a series of vignettes that we patch together to form a unified whole.

It can be hard to let something into your field of vision without thinking it into existence first. To look passively – with your eyes receptive, waiting for the image to come to them rather than thrusting outward to gather what you already expect to be shown. To let the pattern settle on your retina, burning negative space onto darkroom paper. Sharp’s drawings themselves are often quick and spontaneous, but they are the result of many accumulated days and weeks of immersion and consideration. Through these drawings, Sharp connects with a landscape that is not his, but that has found its way into him.

Rebecca Gallo, July 2017

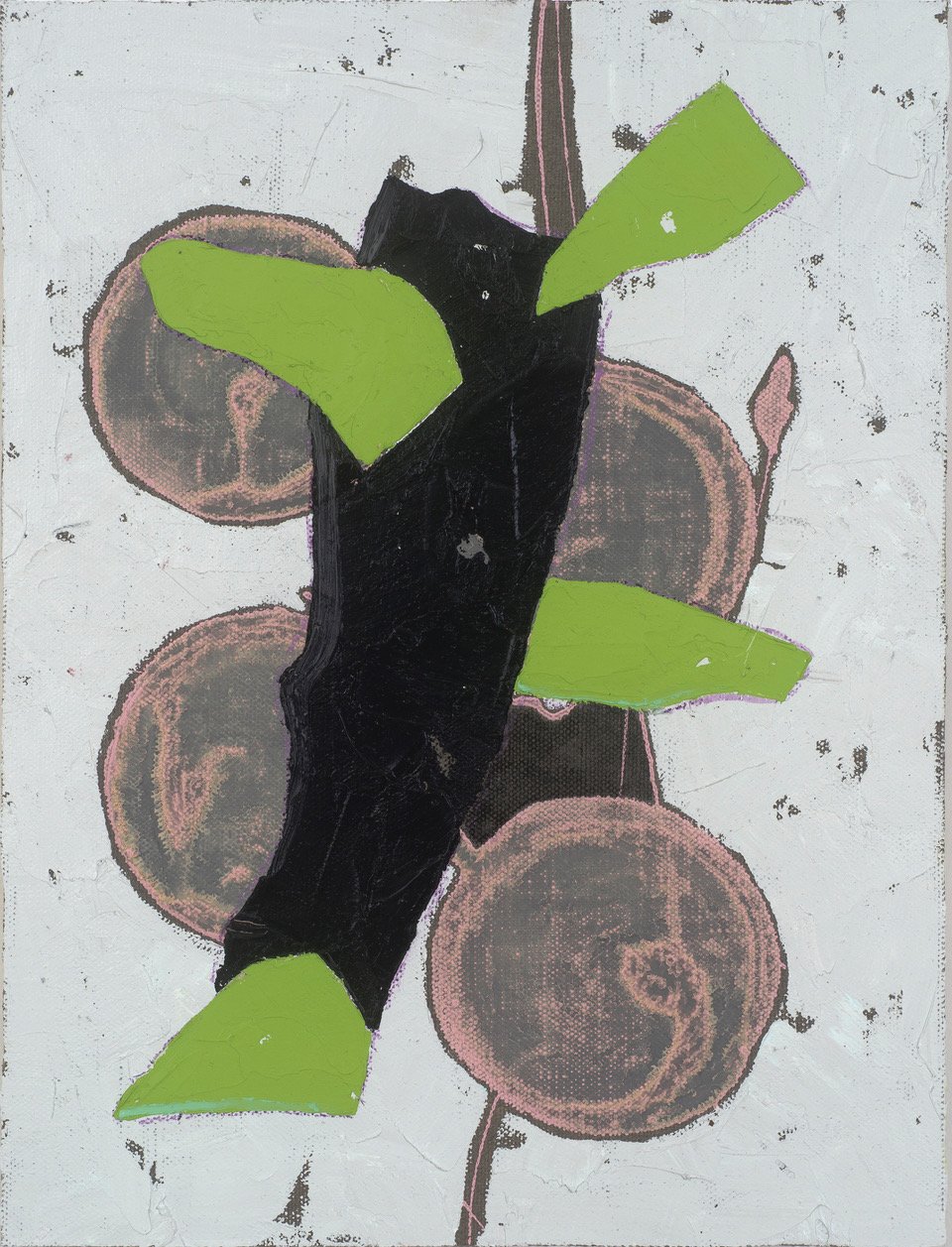

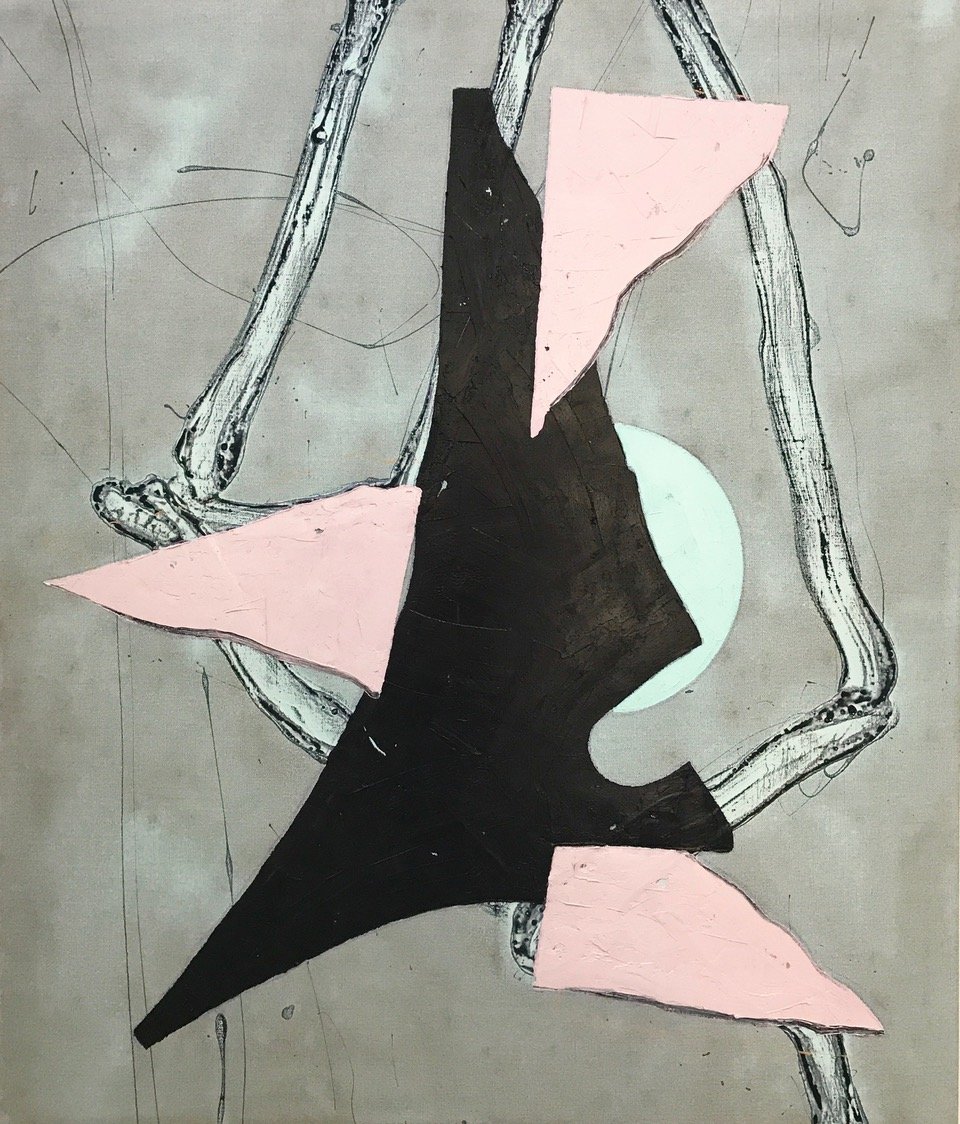

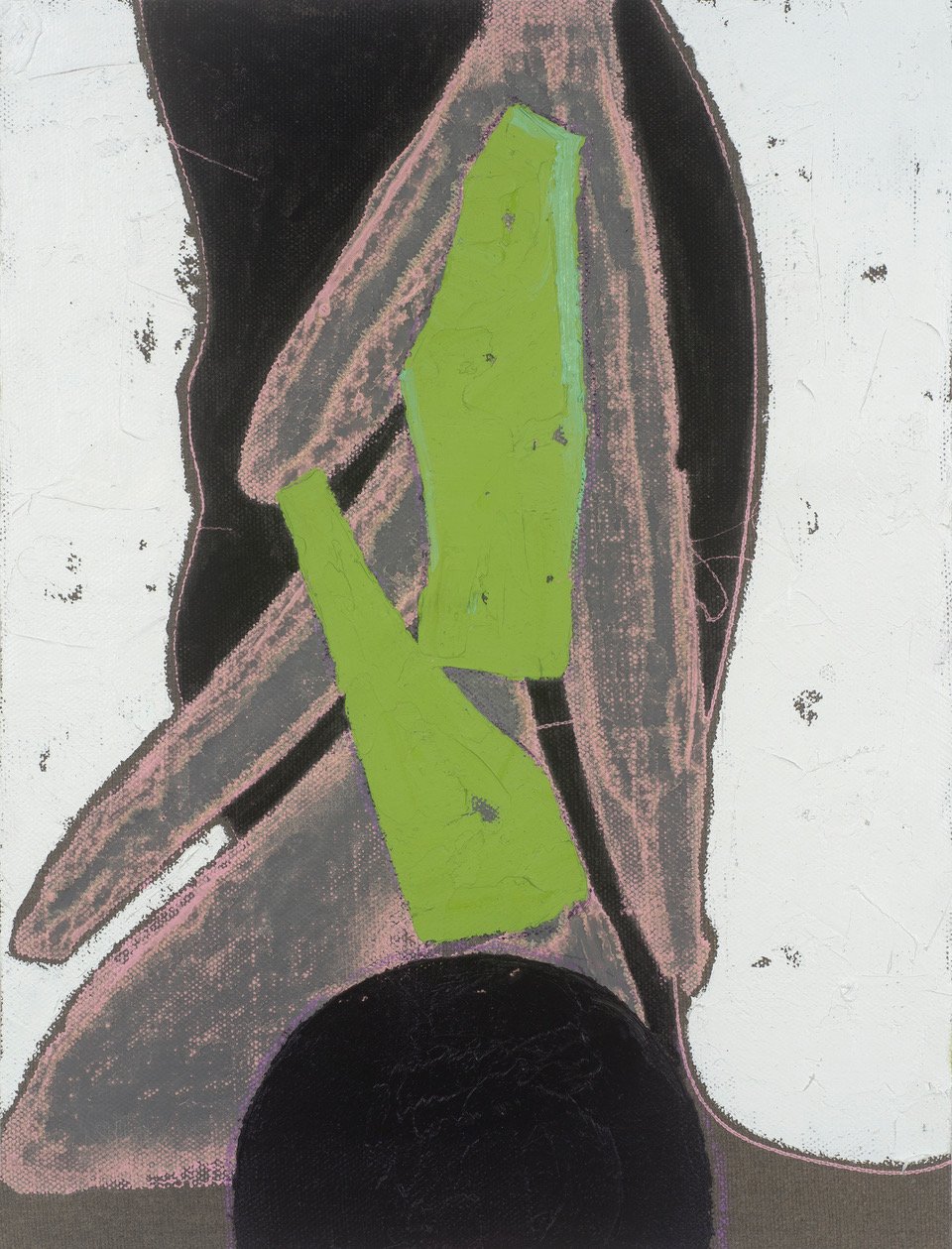

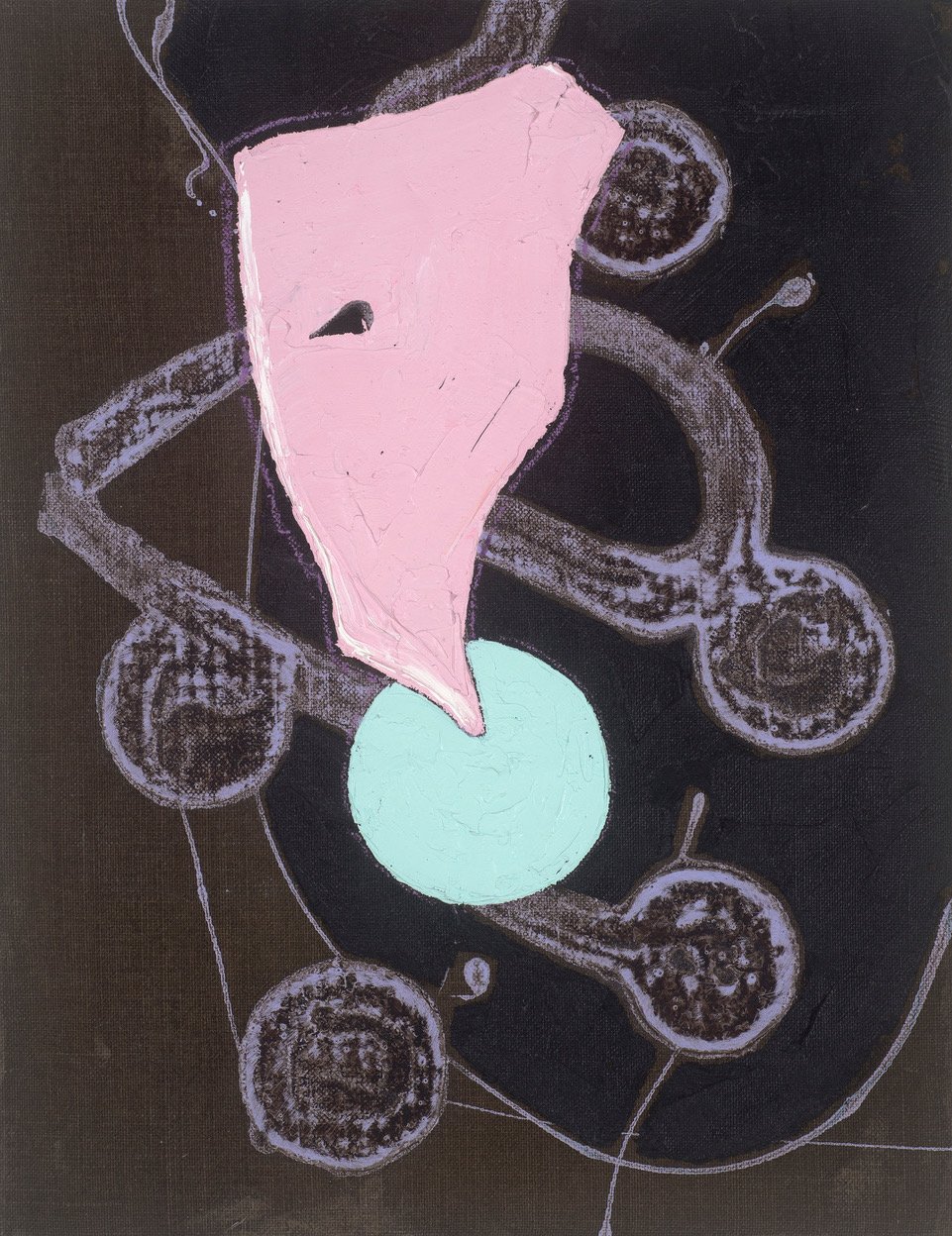

Flowering Gum

Acacia 1

Frond

Acacia 2

Spore

Leaf Litter 2

Casuarina 3

Casuarina 2

Broken Leaf

Study for New Growth 2

Casuarina 1

Night Compass

Night Compass 2

Night Spore