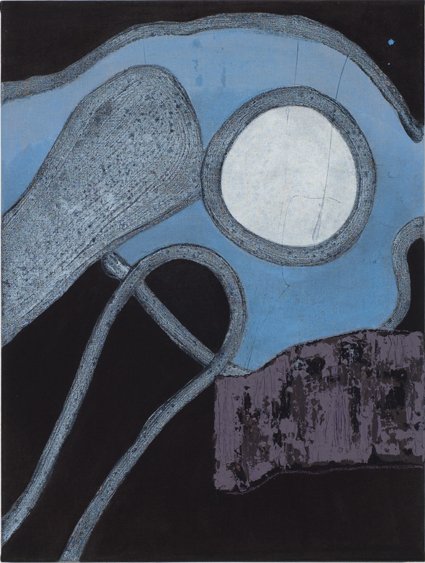

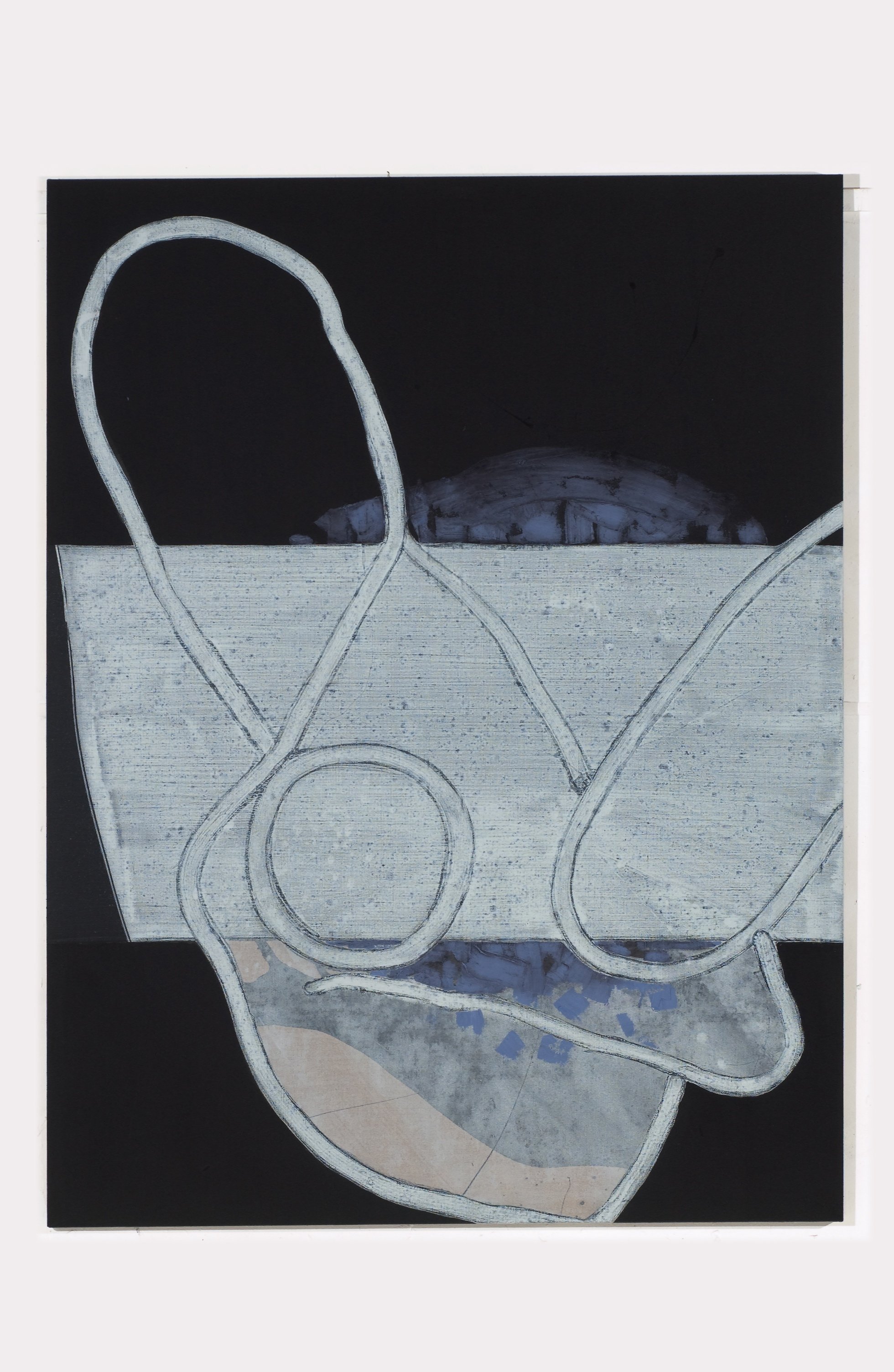

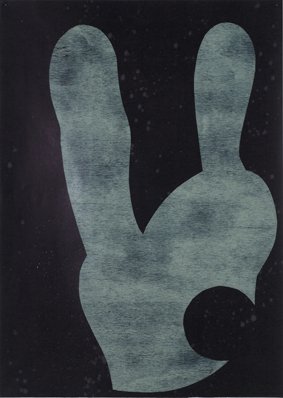

Handle, 2009, oil and acrylic on linen, 213 x 155cm

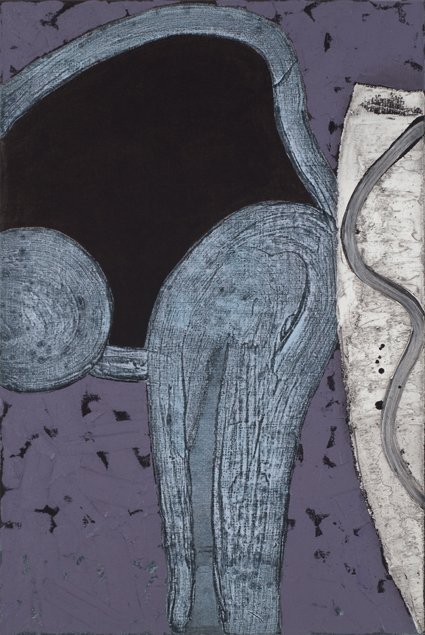

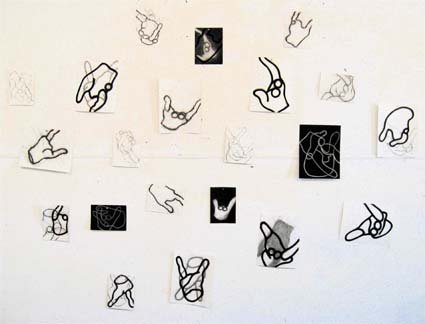

Left to right: Stack, 2009; Pinch, 2009; Fondle, 2009; Caspar, 2009

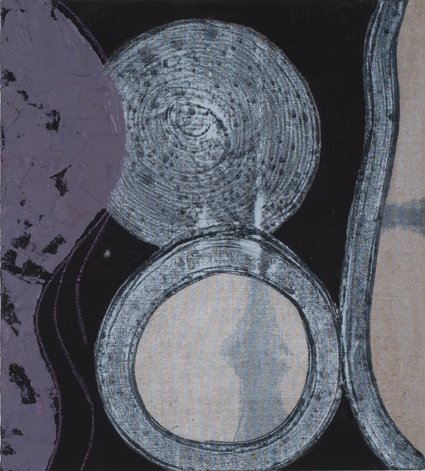

Give and Take 17, 18, and 19

Handle

13 February - 11 March 2010

Liverpool Street Gallery

Hand

Intrinsic to the work of Peter Sharp is the evolution of line. Displaced, abstracted, and skewed beyond recognition, the essential character persistently remains, be it whale or ancient mariner. This is most readily apparent in the suite of monoprints he has produced in collaboration with printmaker, Brenda Tye, where line and form are raw and direct. The paintings, however, deliver Sharp’s astonishing ability to transform a curve or angle into a composition of dynamic activity that denies the figurative while engaging the essence.

For this body of work, Sharp has taken the hand of the Winged Victory of Samothrace (190 BC) as his starting point. Since its discovery in 1863 the winged, but armless statue has become the iconic image of Western art. This is largely due, as André Malraux has argued, to its mutilation, which denied the restorers a definitive position for the arms. In 1950, when the almost fingerless hand came to light, the puzzle was solved; however, the statue had attained such recognition that there was little point in making adjustments. As such, the hand was given its own glass case and plinth, and through Sharp, a new life.

Reduced to a thumb and ring finger, the hand is, like Sharp’s paintings, simultaneously recognisable and remote. Viewed from different angles, the familiarity of the hand within the broken fragment becomes further abstracted, and it is here that Sharp has commenced his deconstruction of the figurative. By isolating sections and truncating angle or line, the drawings Sharp created in the Louvre allow the familiar to slip in and out of our grasp until the work takes on the ‘uncanny’ to scratch at our unconscious.

Sketching many drawings at a time, and causing the Louvre floor to become smeared and littered with charcoal, Sharp absorbed every curve and nuance of the hand’s three-dimensional presence. In doing so he developed a language of line and form, specific to that particular hand, in which he alone is proficient. This is important in understanding his work, as it is not a spontaneous gesture but an inherently known set of shapes that Sharp is drawing on. In effect, it is Sharp’s complete understanding of the hand’s form that allows him so freely to paint these figurative shards from memory.

Using these lines and shapes in their simplest form, Sharp’s eye for composition places them within the frame to intriguing effect. The shapes are amorphous and lineal with subtle plays between positive and negative space. The sea tones of Sharp’s palette exploit this well, with delicate separations and connections playing against one another to push and pull the composition without denying the form itself. Sharp’s choice of medium further disassembles the figurative, with texture and line used in layers of paint and stain, often washed or eroded back to near bare linen. Again the mind recognises the hand, as the layers enfold one set of lines within another in a palimpsest of visual narrative. Sharp’s use of stain as an under-layer for the large painting, Handle, creates a conflict of surface dynamism. The deep brown stain has been dribbled and pushed to a sinuous organic form. Simmering below the surface, washed over and erased, the tendrils of stain should be all but invisible beneath the sturdy lines of the painting’s principal form, yet their presence hauntingly invade the overlaying shapes. This duplicity of tension is fundamental to Sharp’s work, which refuses to let the eye rest on the surface.

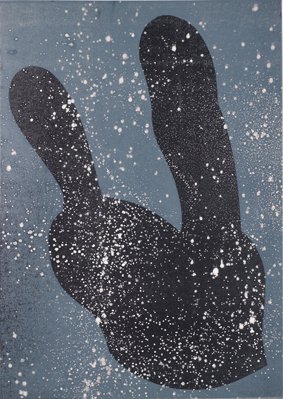

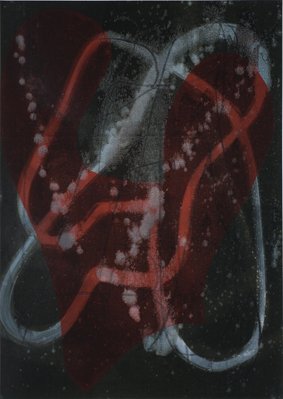

The medium of printmaking plays an interesting role in Sharp’s work, being not only demanding of a confident hand but also an inherent provider of visual tics in the form of bubbles and texture. Give and Take, the series of unique monoprints that Sharp has created for this exhibition, exemplify his use of line and form with robust

simplicity. The Sharp palette is at its most beautiful here, with gentle greens, mauves and greys used to emphasise spatial composition. Tye has been working with Sharp for many years; a proficient and established printmaker in her own right, she works well with Sharp, fusing her feel for the medium with Sharp’s keen sense of line. The simple two-pronged forms are the most recognisable from the Louvre drawings, but like the sculptures, they are also the most removed.

The sculptures, perhaps, are the most literal figurative abstractions of the hand as they physically depict the thumb and finger. Yet their likeness to the hand is the least apparent. This is due largely to the reductive medium of rough-hewn timber, which physically confines Sharp’s use of line to broad strokes. This is not to say that the works are clumsy or obvious; in fact, the opposite is true. Typical of Sharp’s sculptural works, these pieces are elegant and elongated abstractions with a defined sense of stature and linear presence.

Sharp’s work is hallmarked by certain qualities including his use of line and colour, but so too is it recognisable for the deconstruction of figurative elements into abstraction. The amorphous shapes, the language of line, and Sharp’s primordial soup of colour draw the audience to the sea - in this case to a hand found at the bottom of the ocean.

-Gillian Serisier, 2010

Govern

Grasp

Handle

Holder

Knack

Knuckle

Paw

Mitt

Nomen

Pinch

Poke

Give and Take 1

Give and Take 2

Give and Take 3

Give and Take 4

Give and Take 5

Give and Take 6

Give and Take 7

Give and Take 8

Give and Take 9

Give and Take 10

Give and Take 11

Give and Take 12

Give and Take 13

Give and Take 14

Give and Take 16

Give and Take 15

Hands

Caspar

Pinch

Stack

Clasp